Header: ©Ousmane Mbaye

Ousmane Mbaye is a leading name in African design today, but he didn’t get there by sitting in a lecture hall. Instead, he learned his trade on the job, working with his hands alongside his father from a young age. This start in manual work gave him a practical way of looking at objects, where knowing how a material behaves is just as important as how it looks.

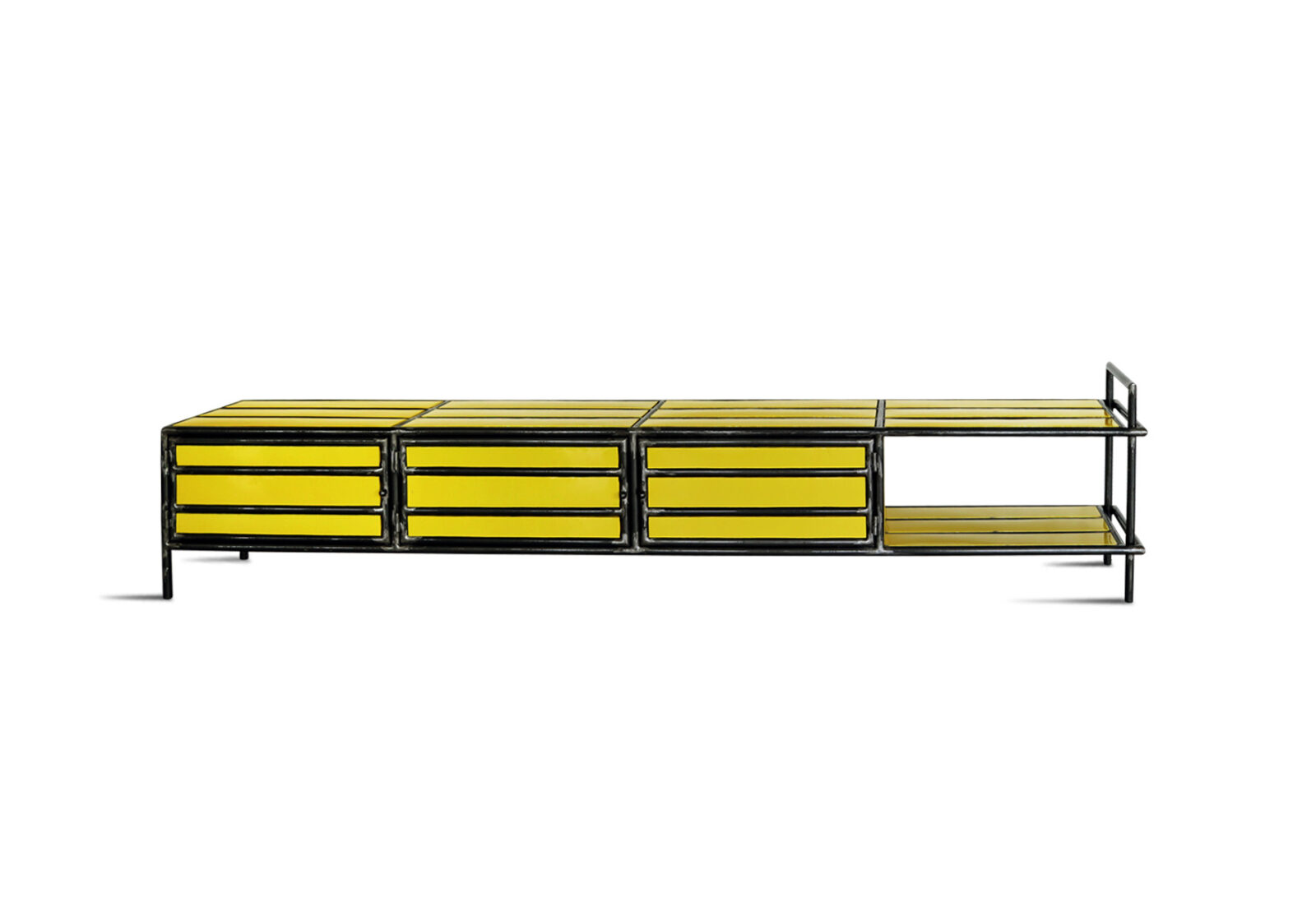

Working mainly with metal, Ousmane creates furniture and lighting that find a steady balance between being useful and making people think. His work is easy to spot thanks to its heavy shapes and bright, fearless use of colour. Beyond just making things look good, he focuses on how objects actually shape our daily lives, making sure sustainability and durability are built into every piece. While metal is his go-to, he is constantly trying out new things with copper and wood to see where they can take his designs next.

Based in Senegal but known from New York to Tokyo, Ousmane is famous for turning tough metals into clean, bright furniture and lights. Whether he is designing a chair or the inside of a busy restaurant, he focuses on making things that last and actually work for the people using them. As a Jury Member of the Africa International Design Awards, he now looks for that same spark of grit and real-world purpose in the next generation of creators.

You were trained in manual trades alongside your father rather than through traditional academic paths. How did that early experience shape your way of seeing and making design?

Being trained in manual trades by my father profoundly shaped my vision of design. From a very young age, I learned to work with materials, to understand their limitations, their resistance, but also their potential. This hands-on approach instilled in me a sense of detail, precision, and above all, a respect for a job well done. Unlike a traditional academic path, this hands-on training taught me that design is not limited to aesthetics: it must be functional, durable, and suited to real-world use. Every object I design must have a reason for existing, meet a concrete need, and fit into the daily lives of its users.

“Decolonising design” is widely discussed today, but how does it translate into the way a space is actually designed, built, and experienced?

For me, it translates into choice, authorship, and proportion. It means questioning why a spatial template exists, who authored it, and who benefits from it. Decolonising design is not aesthetic decoration, it is material sourcing that prioritises local craft economies, proportioning systems rooted in African textile logic, climate-appropriate construction over imported style expectations, and narratives that centre the people who built the land, not those who documented it.

Through your role at the Pan Afrikan Design Institute (PADI), you are shaping how design is taught and understood. What is the biggest shift you still want to see in African design education?

I would like to see African design education stop defending its validity and start defining global futures. We have moved past inclusion; we are at a moment of authorship. The next shift must be an educational ecosystem that recognises indigenous knowledge as methodology, not anecdote, as theory, not folklore.

Your work draws deeply from indigenous knowledge systems. How do you carry tradition into contemporary interiors without turning it into a museum piece?

By allowing tradition to breathe, not perform. I reference indigenous systems as active technologies, ventilation, spatial hierarchy, sonic privacy, thresholds of welcome, not as ornamental motifs. When tradition is treated as wisdom rather than display, it becomes contemporary effortlessly.

Metal has become your signature material, yet you now also work with copper and wood. What draws you to experiment with new materials?

Experimenting with new materials allows me to explore other textures, other emotions, and to expand my creative language. Each material brings a new way to tell a story and enriches my design practice.

Colour is one of the most striking features of your work. How do you think about it when creating a new piece?

I consider colour as a material in its own right. It is considered alongside form to enhance furniture pieces. Like a human being who dresses, we all have a base, but depending on our mood and desires, we choose one colour or another, and this evokes different feelings. Form is the body, and colour is clothing. Colour remains something that can move, change, and evolve, according to the moment, the seasons, needs, or desires.

You’ve spoken about design as a way to improve daily life. When you sit down to create, do you think first about beauty, function, or the message behind the piece?

I take all these different aspects into account from the very beginning. Utility, function, beauty, comfort, and aesthetics all go together. For me, all these aspects come into play from the outset, when I start designing the piece.

From furniture and lighting to hotel and restaurant interiors, your projects touch both private and public life. Does your approach change depending on the space, or do the same ideas guide you everywhere?

The principles remain the same: functionality, coherence, and identity. Only the scale and use of space change, leading me to adapt forms and materials without losing my vision. Human is at the heart of my thinking, whether for private or public spaces.

You have shown your work internationally, from New York to Tokyo, Lagos to Barcelona. How do global audiences respond to your creations, and what do you hope they take away from them?

The first reaction is always surprise, curiosity, and that’s always quite positive. People ask me about the choice of materials and how they were worked, the technique. What touches me most, and what I’m often told, is that it’s a very beautiful way to represent Africa.

As Design Curator for the 2024 Biennale of Contemporary African Art, what perspective did you want to bring, and how do you see design in dialogue with contemporary art?

Design is taking its rightful place in the contemporary creative ecosystem and universe. The line between design and contemporary art is very thin. Each needs the other to express itself and complement each other; it’s a constant dialogue. For 16 years, we didn’t have a design section during the Biennale, and reintegrating a whole section dedicated to design was essential for me; it was important to restore its place in the contemporary artistic debate.

The Africa International Design Awards aim to highlight designers who combine creativity with cultural and social relevance. What excites you about this initiative, and what qualities will you be looking for in the projects?

What I love is that design is often neglected and undervalued in Africa, so any initiative that highlights and celebrates it excites me, and I’m all for it! I look forward to being surprised by the projects, my only expectation is to let people express themselves and discover their vision, what will come of it, and the impact it might have, cultural, economic, social, and so on.

Many young designers in Africa are also starting their journey outside formal education, much like you did. What advice would you share with them about finding their own path and voice in design?

Believe in yourself, listen to yourself, never stop trying, experimenting, doing. It is only through doing that you find your path, your identity, and your voice.