In this interview, we sit down with Beom Kwan Kim to discuss VINE, the project awarded Construction Product Design of the Year at the BLT Built Design Awards. Developed by the University of Ulsan and Studio Kwan, VINE draws from the quiet intelligence of natural growth, translating the logic of climbing vines into a building envelope that generates energy, responds to climate, and reshapes the relationship between architecture and technology. Through AI-driven design, robotic 3D printing, and curved BIPV modules, the façade becomes more than a surface, operating as a living system tested at full scale in Ulsan. Grounded in research yet proven in practice, VINE points toward a future where architectural expression, fabrication, and environmental performance evolve together.

Can you tell us a bit about your background?

My work has always moved between industrial design and architecture. I don’t see them as separate fields, but as two ways of asking the same question: how do we make things that can exist in the real world—technically, socially, and emotionally?

I began studying industrial design in Ulsan, a city where manufacturing and material culture are part of everyday life. That environment taught me early on that design is not only about form, but about systems—production, technology, and application.

Later, I studied architecture at the Architectural Association (AA) in London. AA expanded my perspective from objects to buildings and urban conditions, and introduced me to experimental design thinking and computational methods. At the same time, it strengthened my interest in fabrication, material logic, and the user experience—sensibilities that came from industrial design.

Afterwards, I worked across the UK and Asia on projects of multiple scales, from product and industrial design to architecture and urban work. Those experiences reinforced my belief that architecture is not simply spatial composition, but an integrated process where materials, technology, environment, and human life converge.

Today, at the University of Ulsan, I continue to teach, research, and practice in parallel. My focus is on computational design, material experimentation, robotic fabrication, and renewable energy systems—especially research that is site-specific, experimentally validated, and scalable, rooted in local environments and regional industrial technologies.

What is the inspiration behind VINE, and what problem were you trying to solve?

VINE began with a simple but fundamental question: What should the role of architects and designers be for the next generation? I wasn’t interested in making something that was only creative or visually pleasing. I wanted to ask what kind of design is actually necessary today, given the relationship between people, cities, and the environment.

Conceptually, VINE is inspired by the way vines grow: starting from the earth, climbing surfaces, and reaching toward light. That natural logic helped me reinterpret the building envelope as something more than a boundary—more like a living, responsive skin of the city.

The practical problem was also clear. Conventional flat BIPV panels often underperform on façades, they limit architectural freedom, and they tend to remain as attached technical devices rather than integrated architectural elements. So we asked:

What if a building envelope could grow like a living organism—respond to the environment—and generate energy by itself?

VINE is our experimental and empirically validated response. It integrates natural growth logic with AI-based design, robotic fabrication, and renewable energy into one architectural system.

How would you explain VINE simply to someone unfamiliar with BIPV or 3D printing?

When people hear “BIPV” or “3D printing,” they often assume it’s complicated—so I begin very simply. VINE is a façade that behaves like a vine reaching for sunlight. The building’s outer skin doesn’t just sit there; it reacts to light.

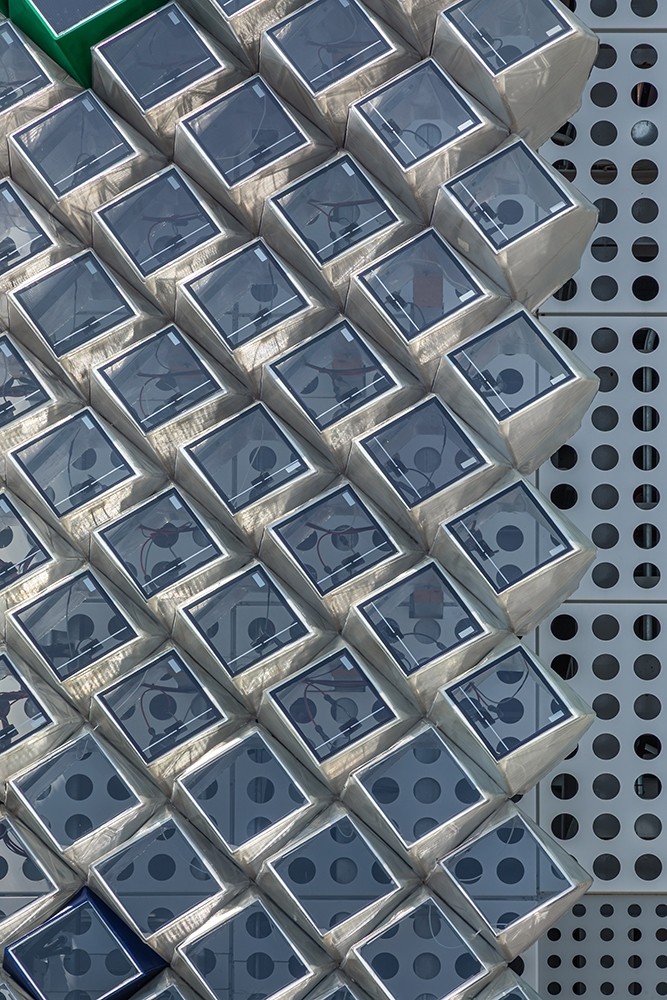

Most solar panels are flat, and on vertical walls, they struggle to catch sunlight efficiently. VINE replaces that flat logic with many small, curved, multi-angled modules, creating a textured skin. Because each module faces the sun a little differently, the façade captures light more effectively—especially in summer.

And VINE doesn’t stop at generating energy. It is designed as a system that absorbs sunlight, produces electricity, stores it, and reuses it when needed—so the building can operate more like a self-sustaining organism than a passive structure.

The modules are made with large-scale robotic 3D printing, enabling complex curved shapes without moulds and using eco-friendly materials such as biodegradable PETG and recycled plastics. On-site, it works like modular cladding: easy to install, easy to replace, and practical to maintain.

How did you develop the geometry so it can be mounted on real buildings?

Honestly, this was one of the most difficult parts. The project started from an intuitive idea—an organic, non-linear geometry integrated with photovoltaics—but turning that into a buildable system is a different problem entirely.

Form changes directly affect solar performance, structural stability, and constructability, so the geometry could not remain arbitrary. We needed integrated research where geometry, performance, and construction details could be resolved at the same time.

That is why we developed an AI-based design tool that analyses EPW climate data, solar paths, shading conditions, and orientation. Each module is generated and adjusted based on those inputs. In that sense, VINE’s geometry is not simply an aesthetic gesture—it is data-driven and performance-based.

In parallel, we developed a hybrid structural system combining steel and timber, along with standardised connection details. Through repeated prototyping, testing, and validation, the façade evolved into a modular system that remains complex in appearance but feasible in construction.

How did robotic 3D printing enable the curved multi-angle modules?

Large-scale robotic 3D printing was a key technology for VINE. Conventional BIPV production is based on mould-driven flat manufacturing, which fundamentally restricts curved and multi-angled geometries. Robotic fabrication allowed us to move beyond that limitation.

Without moulds, we could fabricate non-linear curved modules with precision. Using a multi-axis robotic arm, we controlled extrusion angles, thickness, and local transparency to guide daylight, reduce self-shading, and maximise solar incidence according to orientation and sun angles.

VINE is not a repetition of identical panels. It is a parametric family of modules—unique in geometry, but unified as one buildable system. In the prototype and demonstration, around 136 modules were installed, each generated through multiple parametric variables..

Material choices were equally important. We used biodegradable PETG and recycled industrial plastics so that sustainability is embedded not only in the idea but in the manufacturing process itself. In that sense, robotic 3D printing became an architectural production strategy integrating geometry, performance, material, and environmental responsibility.

How did sun-path studies guide the design, and how did you achieve such high summer performance?

In VINE, sun-path analysis was not a final check—it was the starting point. We didn’t design a form and then optimise it; we allowed solar behaviour to generate the form.

Using EPW climate data, seasonal sun paths, solar altitude/azimuth, and shading simulations, we informed not only the overall façade direction but also each module’s local angle, curvature, depth, and spacing. That is why every module is differentiated by its position and exposure.

Summer performance was especially important. When the sun is high and intense, flat BIPV systems often suffer from inefficient incidence angles and thermal losses. VINE addresses this with multi-angled curved geometry that receives solar radiation more orthogonally across the day while reducing self-shading.

The differentiated geometry also creates micro-gaps for ventilation and micro-shading, helping dissipate heat and reduce thermal buildup—a major cause of efficiency drop in summer conditions.

In short, sun-path studies did not optimise a fixed design; they generated a responsive, climate-aware energy façade.

How is VINE made and assembled on site?

VINE was designed as a buildable and maintainable system from the beginning. Fabrication, assembly, and maintenance were not afterthoughts—they were part of the design.

Modules are fabricated off-site using large-scale robotic 3D printing. Each geometry is generated through an AI-based workflow and translated directly into robotic fabrication data. This enables complex forms without moulds, while maintaining precision. Around 136 unique modules were fabricated for the demonstration system, all different in shape but unified by one structural logic.

After printing, modules are combined with standardised photovoltaic components and connection interfaces, pre-assembled into transportable units, and delivered to the site. This prefabrication reduces on-site time and minimises construction errors.

On-site, a hybrid structural frame of steel and timber is installed first. Modules are then mounted using standardised mechanical connections. Because each module is digitally indexed, installation remains systematic even when no two modules are identical.

Maintenance is equally modular: each unit can be detached and replaced independently, and PV components are accessible for inspection and service. VINE is therefore scalable, replaceable, and serviceable—connecting experimental geometry with long-term operation.

What were the main challenges, and how did you resolve them?

The hardest part of VINE was meeting three demands that usually conflict: sculptural freedom, renewable energy performance, and manufacturability. Expressive geometry can reduce efficiency, while performance-driven solutions often become formally restrictive. For this project, choosing one at the expense of the others would have weakened its purpose.

We treated these constraints not as competing priorities but as conditions that must inform each other. That required a long, iterative process: AI-based solar simulations, parametric adjustments, structural analysis, and physical prototyping—repeated many times.

Collaboration with engineers was essential. A buildable system needs more than algorithms; it requires structural logic and realistic construction strategies. Through that collaboration, we developed a hybrid structural system and standardised details that preserved complexity while remaining feasible.

Finally, validation mattered. VINE needed to work in real conditions, not only in simulations. The Ulsan demonstration at HD Hyundai Construction Equipment became the turning point—allowing us to verify energy output, structural stability, and economic viability at once. That real-world proof shifted VINE from an experimental idea to a credible architectural energy system.

How do you feel about receiving the “Construction Product Design of the Year”?

Receiving “Construction Product Design of the Year” is an honour, but more importantly, it feels like recognition of an approach rather than a single object. VINE started as a question: can a building envelope become an active system—responsive to climate, generating energy, contributing to its surroundings—rather than a passive surface?

Being recognised in a construction product category is significant because it suggests that research-driven and experimental ideas can transition into buildable, scalable systems. What makes the award especially meaningful is that it acknowledges not only formal innovation, but also performance, manufacturability, and real-world feasibility.

VINE was developed through extensive prototyping, AI-driven simulations, robotic fabrication, and on-site demonstration in Ulsan. The fact that its energy output, structural stability, and economic potential were validated gives this recognition real weight.

Personally, it also resonates with my background across industrial design and architecture. It reassures me that working across disciplines can produce new possibilities for future building systems.

How will VINE influence your future work, and what advice would you give young designers?

I don’t see VINE as a conclusion. I see it as a point along a longer process. The project reaffirmed my belief that architecture today must be developed as integrated systems—where performance, technology, material, and environmental responsibility are designed together, rather than treated separately.

I’m also not sure I’m in a position to give advice. I still feel that I am learning, questioning, and searching in much the same way as many younger designers. What I can share is an experience: that ideas only become real when they are tested under real conditions.

The demonstration project in Ulsan was a turning point for me. Building the system, measuring its performance, and validating it on site shifted the work from speculation to evidence. Going forward, I hope to continue developing projects that combine computational design, material experimentation, robotic fabrication, and renewable energy systems—always grounded in implementation and verification.

Through the process of submitting this work to competitions and external reviews, I also realised how important it is to test ideas beyond one’s own discipline, context, or environment. Having work evaluated from different perspectives—technical, cultural, and geographic—often reveals questions and insights that are not visible from within a single field. For me, this kind of external validation has become an essential part of design research.

If there is one thing I would like to share, it is this: you don’t need to start with definitive answers. What matters is having questions that feel necessary, and staying with them long enough to test them thoroughly. I hope these explorations become collective—shared with architects, designers, and researchers across different fields and countries—because that is where the future of architecture and design truly begins.

Finally, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the BLT Awards jury and organising committee for recognising this work and for providing such a meaningful platform for dialogue. This opportunity to share the ideas behind VINE through the award and this interview is deeply appreciated.