Header: James Brittain

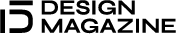

Montreal-based studio Pelletier de Fontenay recently unveiled the new Botanical Garden’s Entrance Pavilion. In conjunction with the metamorphosis of the Montreal Insectarium and the transformation of the entrance to Parc Maisonneuve, this project offers a redesigned and modernised access hub for this emblematic site. The new pavilion welcomes visitors, facilitates ticket sales, and provides information on the Botanical Garden and Insectarium. It also includes a smaller, separate check-in kiosk.

Developed in collaboration with a team of landscape architects from the City of Montreal’s Urban Parks Division, and the firm Lemay, the vision serves to link the world of Maisonneuve Park to the front court of the newly completed Insectarium. The project’s main challenge was to better orient and guide visitors towards the Insectarium and Botanical Garden while respecting the cultural heritage of the site.

Romance, History, and Architecture

In studying the long history of park and garden pavilions, Pelletier de Fontenay’s team focused on the notion of the ruin as a bearer of several ideas that resonate with modern-day issues. A recurring theme in 18th and 19th-century English gardens, the image of the overgrown ruin is deeply rooted in the romantic movement, which asserts the superiority of untamed nature, the imperfect, the sublime, and the overall nostalgia of a lost natural world. Architectural structures, once colonised by vegetation and other forms of life, propose a symbiosis between the built and the living world, a productive relationship in which architecture becomes a literal support for life.

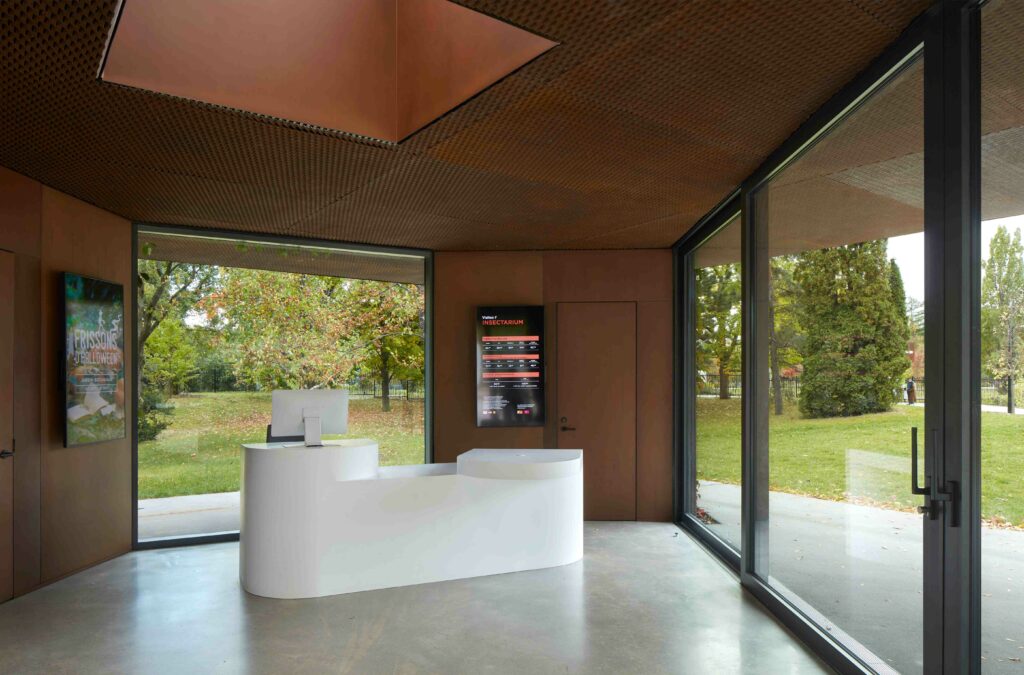

Much like a romantic ruin invaded by plants, the Montreal Botanical Garden’s Entrance Pavilion stands as a hybrid figure where architecture and nature meet. Humbled to its pavilion scale, the building, once fully covered by vines planted at its base, will become an infrastructure welcoming insects, birds, and small animals.

The design

Visible from both Parc Maisonneuve and the Insectarium, the new reception pavilion is strategically positioned at the inflection point of the approach route. Its triangular plan is designed both to create a focal point in the landscape and to manage the flow of traffic: one enters on one side and exits through the other, in a natural pathway towards the entrance to the Botanical Gardens and the Insectarium. At the base of the volume, the triangle’s corners form the pillars that support a wide, square-shaped roof. The interaction of the two geometries produces generous roof overhangs, offering protection from the sun and weather. The entrance and exit areas become sheltered meeting points or places to queue up during busy hours.

The large roof, which extends from interior to exterior, supports the notion of landscape continuity. As soon as spring temperatures permit and until mid-autumn, the pavilion’s large sliding doors can remain open, eliminating the boundaries between inside and out. The ability of the building to open wide to the landscape is fundamental to Pelletier de Fontenay’s approach to this project. Visitors can feel the wind and heat, hear the birds, and smell the nearby forest while they plan their visit, obtain tickets at the digital terminals, or get information at the counter. From a bioclimatic standpoint, being in tune with the weather also means that for a good part of the year, there is no need for heating or air conditioning.

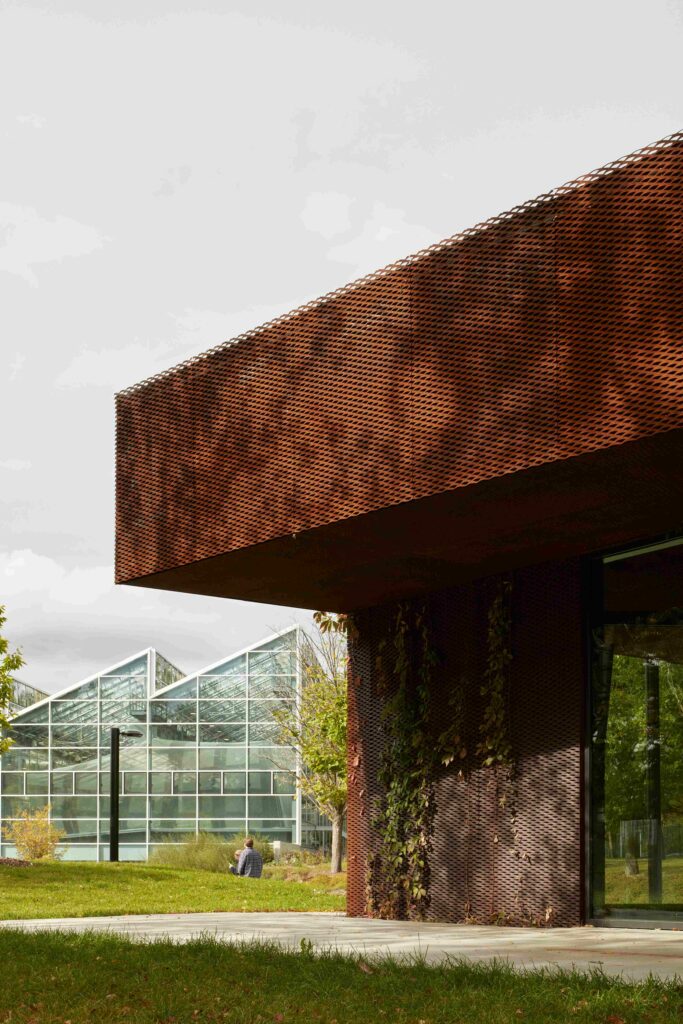

The assembly and superimposition of two simple shapes—the triangle and the square—convey a primitive quality to the overall structure. Far from emphasising its construction, the pavilion’s tectonics are completely sublimated in favour of a single-material skin that covers all surfaces homogeneously. This skin is made entirely of expanded corten steel, except for the vertical interior faces, where the steel is left smooth. The project goes against the idea of architecture as assemblage, as a mere technical expression. Instead, constructive articulations make way for a more monolithic, enigmatic, and archaic representation. Conceptually, visitors might well get the impression that the structure predates the garden that now surrounds it.

The use of corten steel supports the idea of a structure worn and weathered with time. The expanded structure of the sheets provides an ideal support surface for vining plants, and the size of the openings is calibrated to allow them to navigate on either side of the skin, entering the architectural cavity in some places only to emerge higher up. As the corten steel cladding gradually oxidises and the structure is colonised by climbing plants, the pavilion’s appearance will evolve, evoking a ruin gradually overtaken by nature, and thereby entering a symbiotic relationship with it.