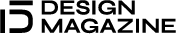

As a design magazine, we often write about beauty—the beauty of objects, space, and form. But sometimes, design is at its most vital when it steps into discomfort, history, and the gaps left by silence. Unsilenced: Sexual Violence in Conflict, now open at IWM London, is one such exhibition, designed not for spectacle but for stillness, careful witnessing, and emotional intelligence. Created by Nissen Richards Studio, the graphic, spatial, and material design becomes not just a backdrop but an instrument of care.

Free to enter and open until 2 November 2025 at IWM London, Unsilenced is the first exhibition by a major UK museum to confront this topic head-on. Recommended for visitors aged sixteen and over, it aims to inform, empower and ultimately contribute to meaningful change.

Through more than 160 objects, many never publicly shown before, alongside testimony, photography and archival material, the exhibition explores how sexual violence manifests in conflict and how propaganda shapes gender and power dynamics. It sheds light on the experiences of evacuees, prisoners of war, victims of trafficking and survivors of conflict-related sexual violence from the First World War to the present day, while also highlighting those working tirelessly to fight for justice and prevention.

Design Language

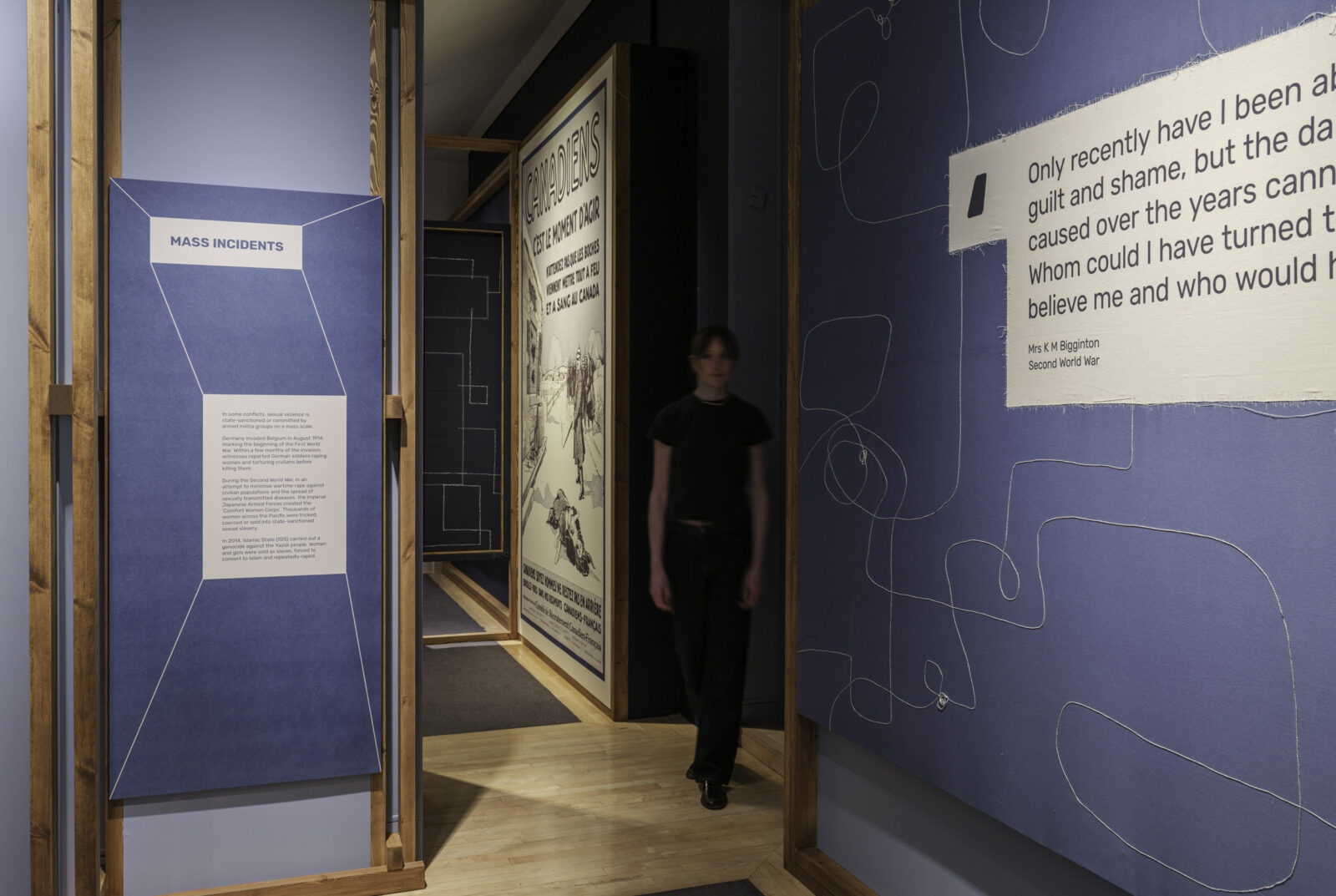

“Because of the distressing nature of the subject matter and testimonies in this exhibition, we sought above all to create a very calm and clear exhibition design language that would support visitors and respect the impact of the stories being told,”

Pippa Nissen, Director of Nissen Richards Studio, commented.

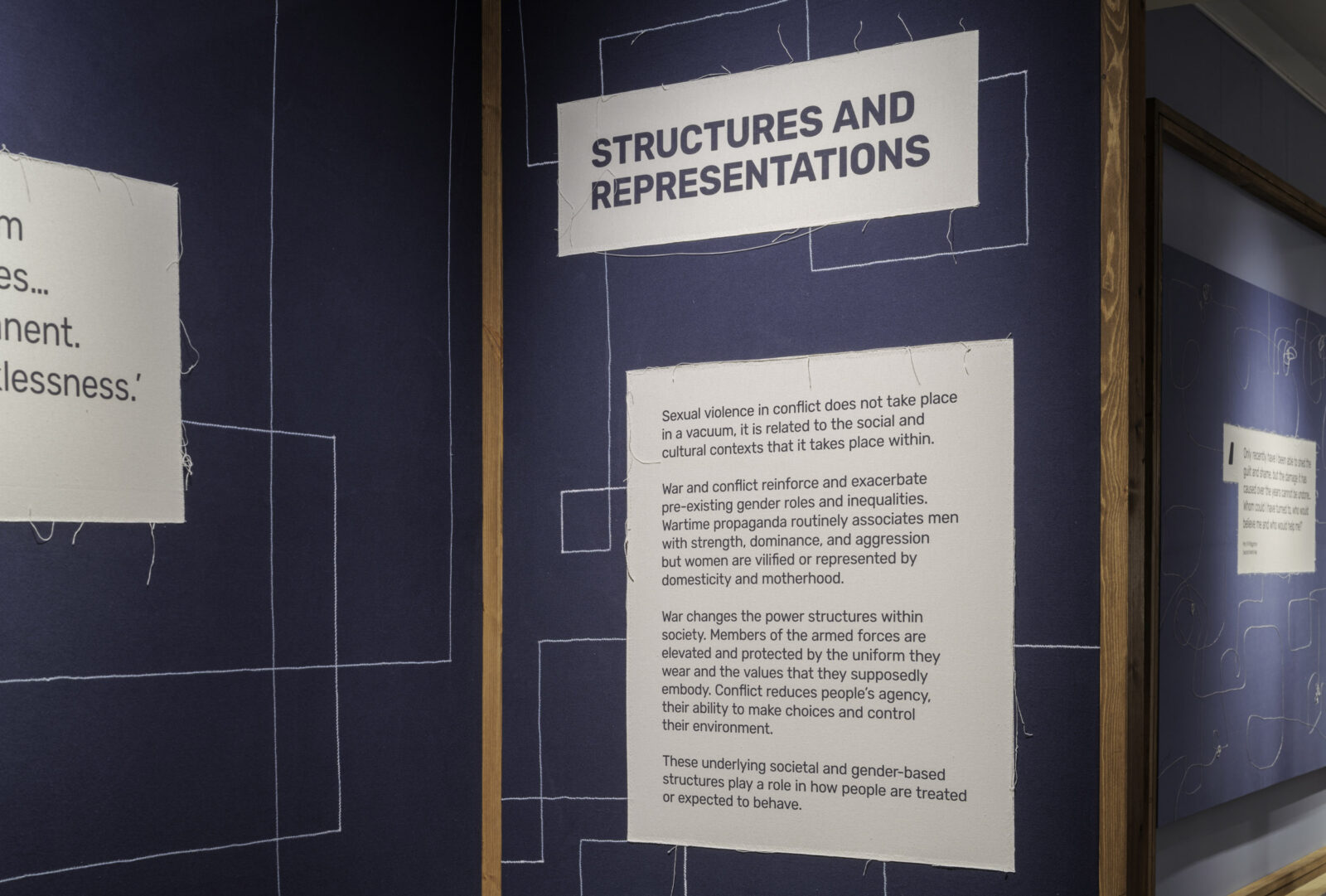

Graphic communication uses gauzy panels, suggesting transparency, set into rich timber frames, which talk of the weighty subject matter. The design language includes layering, which changes throughout the exhibition in terms of materiality but makes the build feel light and transparent. The layers also provide levels of complexity and subtlety in relation to the subject matter, allowing connections to be made. The exhibition design features a progression of colour from darker tones of blue to lighter, warmer and more neutral colours, expressing an emotional shift as the exhibition progresses.

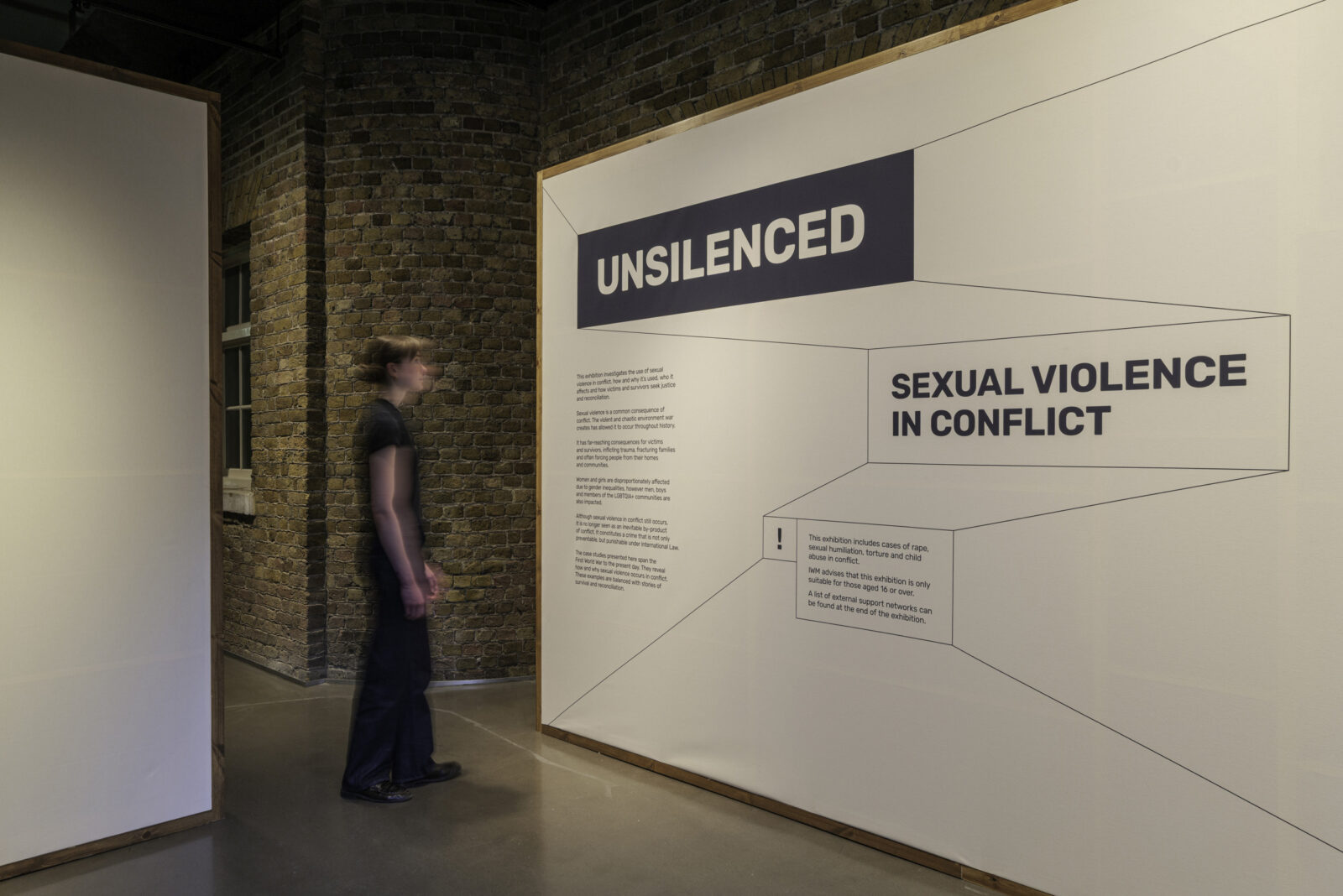

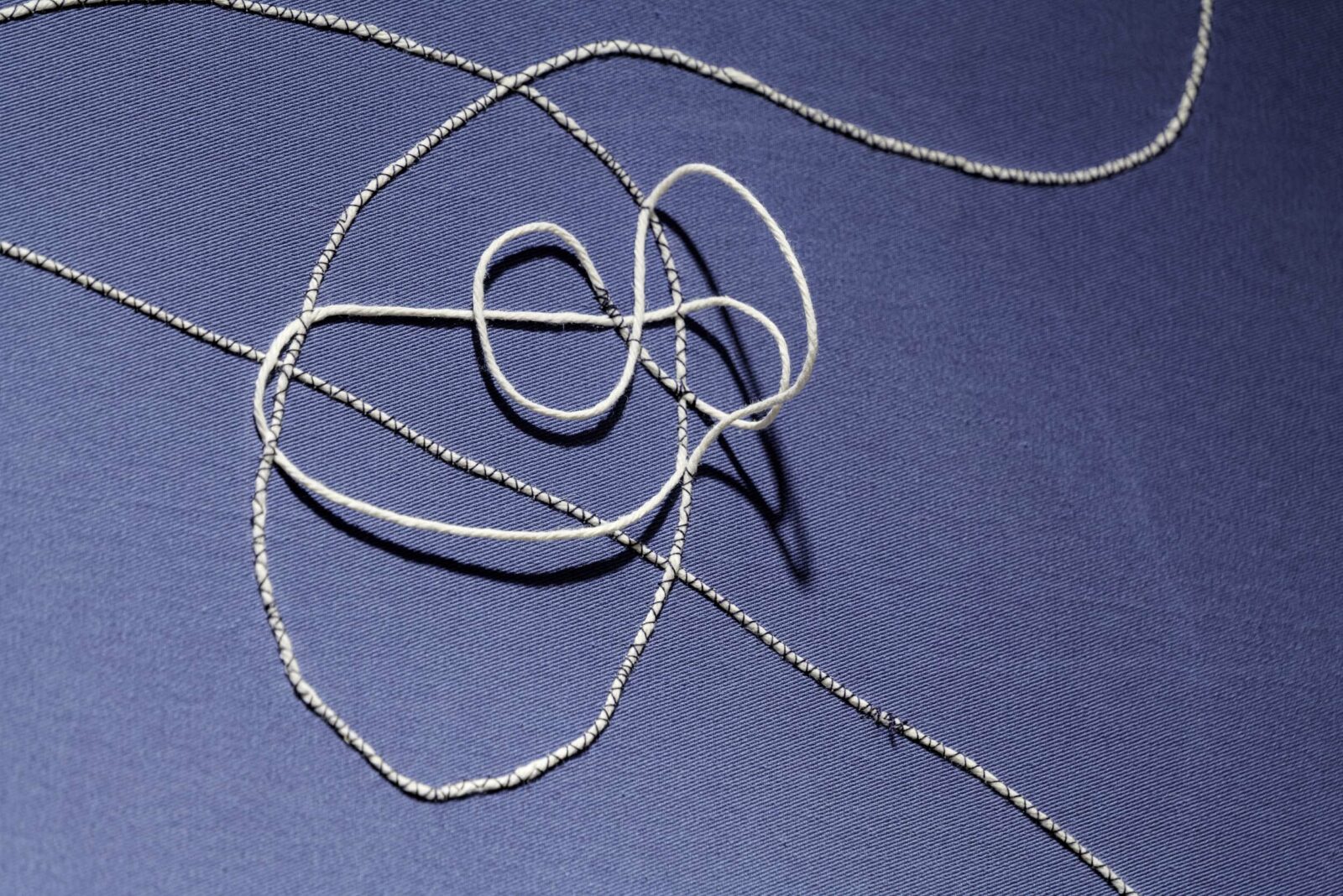

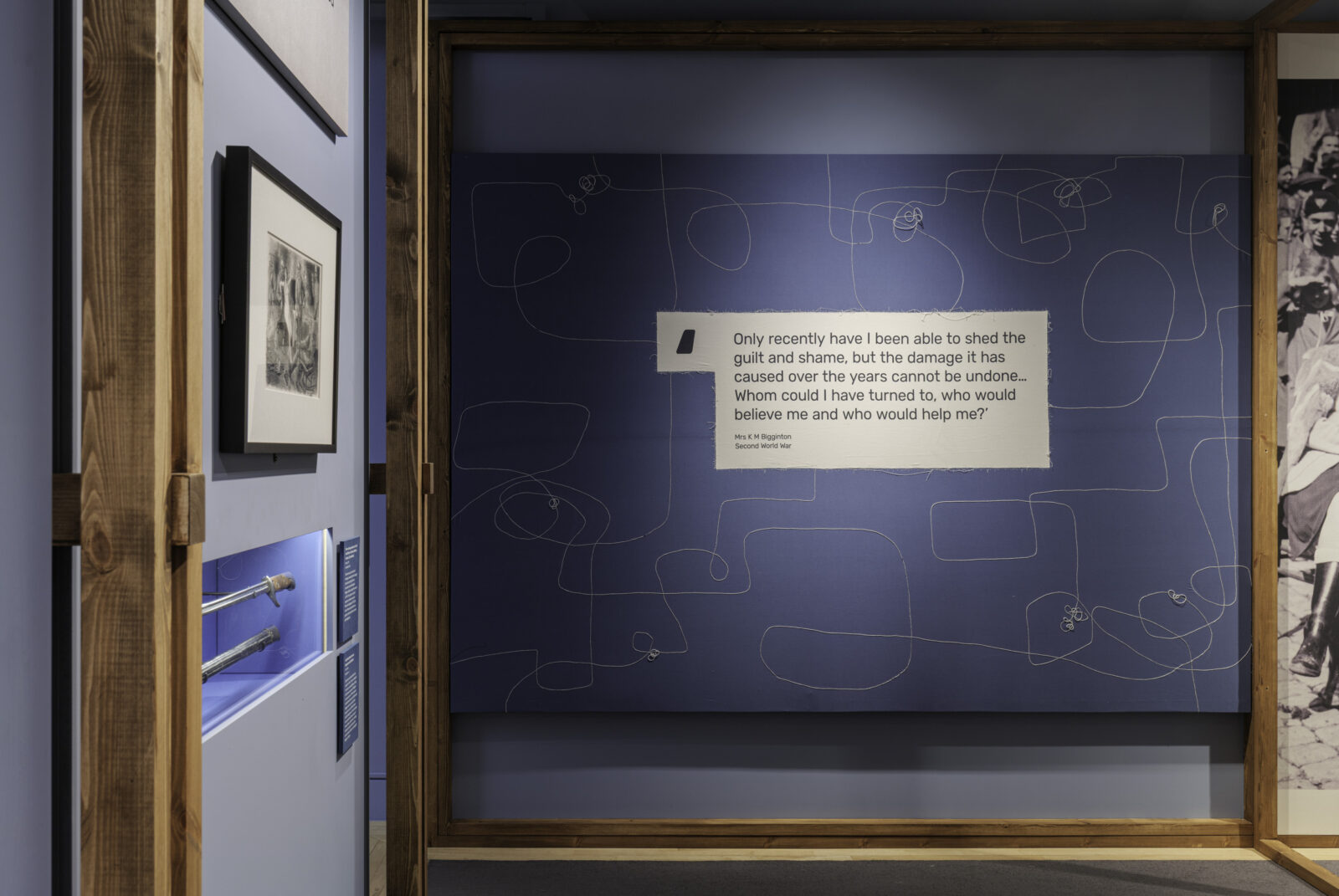

The other major creative feature of the exhibition design language is using textiles and embroidery to add a softer, more human, and tactile aspect to help set the exhibition’s tone. Nissen Richards Studio liaised with The London College of Fashion to select a current student to work with on this. The collaboration between the design team and student Yi-Ching Wang – who had done a master’s thesis on this subject – sees fabric and thread used in abstract ways in the place of traditional graphic panels, with the IWM’s interpretative text printed onto canvas and then sewn into a fabric surrounding the panel, where the beautiful sewn line work expresses each room’s theme. Whilst the lines used are linear for room one, for example, they become tense and agitated for room two, and more organic in room three.

“This process allowed us to push the boundaries of interpretation to express ideas in more metaphorical ways,” Pippa Nissen added. “The work created through this collaboration adds a directly emotional aspect to the exhibition that speaks of the power of free expression and repair, as well as war’s chaos and the unravelling of social norms.”

Themes

The thematic structure of the exhibition includes an introductory AV space, followed by three main rooms whose themes are:

- Structures and Representations

- Acts and Manifestations

- Justice and Reconciliation

Two further spaces are the NGO room, which examines the work done by organisations caring for and working with the victims of sexual violence in conflict, and a final contemplation and reflection room.

The exhibition’s thematic treatment, whilst representing only a fraction of a huge and complex subject, nonetheless investigates conflict across a wide time period, from the First and Second World Wars to the Gulf War, the Bosnian War, the Ukraine War, the Iraq War, the Balkans War, the Sudan War, and the Yazidi Genocide. Although the victims of sexual violence in conflict are overwhelmingly female, the exhibition also tells of male and child victims, looking not only at rape but at state-sanctioned sexual violence, humiliation and slavery within conflict contexts.

“Sexual violence is a devastating aspect of conflict and very difficult to talk about. This silence creates significant barriers to recovery, justice and lasting change. Survivors face immense challenges in sharing their stories, while the public lacks the knowledge or language to talk about these issues with confidence. By raising public awareness and deepening understanding of sexual violence in conflict, Unsilenced aims to inform visitors, empower survivors and contribute towards meaningful change in the fight against sexual violence in conflict.”

Helen Upcraft, Lead Curator of Unsilenced: Sexual Violence in Conflict.

Finding 3D objects directly linked to the exhibition’s themes was not an easy task, forming part of the silence that has historically surrounded this subject, and so the exhibition features a mix of written and oral testimony, historic posters, photography, totemic objects, and works of art. These include a painting by South African artist Albert Adams, photographs by Lee Miller and a miniature Sonyeosang (Statue of Peace) copied from a 2011 bronze by husband-and-wife sculptors Kim Seo-kyung and Kim Eun-sung.

Walk-through

The exhibition opens with a quiet but powerful AV space, where visitors are introduced to the topic through newly created film interviews. These aren’t abstract theorists, they’re the voices shaping how we understand gender, conflict, and justice today: Christina Lamb, Chief Foreign Correspondent at The Sunday Times; Dr Paul Kirby of Queen Mary University; Dr Zeynap Kaya from the University of Sheffield; Sarah Sands, former Chair of the G7 Gender Equality Advisory Council; and Charu Lata Hogg, Founder of All Survivors Project. Their presence sets the tone: informed, compassionate, urgent.

From here, visitors step into the first main gallery—Structures and Representation—where the groundwork is laid. High-impact visuals dissect the propaganda of war, making visible how sexual violence is scaffolded by the way societies view gender. Women are shown as either fragile and in need of saving, or dangerously seductive; men, meanwhile, are cast as either protectors or monsters. The stereotypes aren’t just relics, they’re ideological weapons. This room connects image to implication, showing that violence doesn’t begin with the act, but with the narrative.

In the next space—Acts and Manifestation—the stories are harder, more direct. It’s here that we encounter individual accounts of rape, abuse, sexual slavery, and coercion, from WWI Belgium to the horrors inflicted by ISIS. The infamous ‘comfort women corps’ and the sexualised torture of male prisoners in Abu Ghraib are part of the timeline. It’s a confronting room, yes, but thoughtfully paced. Design elements create pause points: alcoves and corners where visitors can stand, absorb, and breathe before continuing.

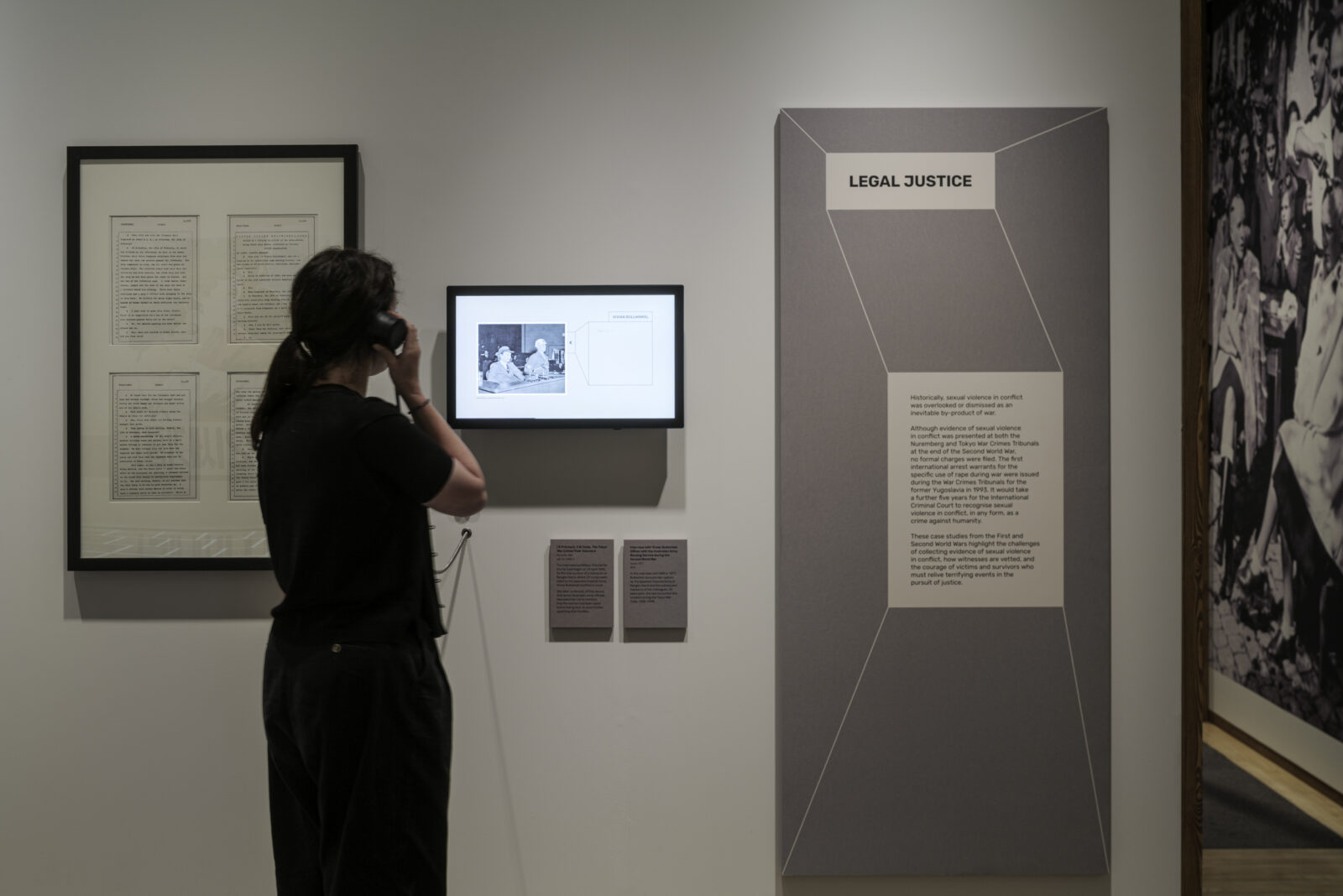

The third thematic gallery—Justice and Reconciliation—shifts the conversation again. There are legal cases, instances of progress, and brutal reminders of how rare justice still is. The children born of wartime rape in Bosnia are present here—visibly and powerfully—as are the absences: the crimes ignored at Nuremberg and Tokyo. This space doesn’t claim closure, but asks how accountability can look when silence is the default.

Beyond the core narrative, the exhibition widens its lens to spotlight ongoing work on the ground. A space dedicated to four NGOs—Women for Women International, All Survivors Project, Free Yezidi Foundation, and Waging Peace—offers glimpses of healing and rebuilding. Visitors see a Sudanese toub stitched with fragments of testimony, a toy handmade by Yazidi women, and photography by Hazel Thompson that captures both grief and grit. These are not just displays, they’re expressions of survival and resistance.

Finally, the exhibition closes as it begins: with space. The final AV room echoes the voices from the opening—looping reflection, not conclusion. It invites visitors to sit with what they’ve learned, and more importantly, what they feel.

In architecture and exhibition design, the word “sensitive” is often overused, but in Unsilenced, it feels essential. Every thread sewn, every panel suspended, every shift in hue is a deliberate, quiet gesture carrying heavy stories. In stepping into this space, we’re not just learning history; we’re feeling its weight and its refusal to remain unspoken.

For those of us who believe design has the power to shape not just environments, but understanding, this exhibition is a rare and deeply moving reminder.

Images: Gareth Gardner