Header: Wolfgang Laimer

When the Global Footwear Awards announced its latest winners, one of the more unconventional entries stood out in the sustainability and running footwear categories. Rapid Autograft, a student project by designer Wolfgang Laimer, proposes a speculative approach to performance footwear by integrating biotechnological processes directly into the shoe’s design. Developed during his studies at Konstfack, the unique sneakers explore how advancements in tissue engineering might change long-distance running.

In this interview, Laimer reflects on the development of Rapid Autograft, from material research to design philosophy. He discusses the challenges of working with speculative concepts, the influence of his academic environment, and the broader questions raised by designing at the intersection of biology, technology, and human performance.

Can you tell us about your background? How did you discover your interest in design, and what would you say is your personal design philosophy?

I work between disciplines, methods, and perspectives. My path has taken me from carpentry to industrial design and design ecologies, alongside my studies in analytic philosophy. Designing footwear is particularly appealing to me because it uniquely combines function, culture, and identity. As an ultra-trail runner, I also understand the precision that footwear demands. I may not come from a traditional shoemaking background, but I greatly respect the craftsmanship and heritage of this field.

My work is not just about solving specific problems or creating beautiful objects, but also about challenging perspectives. Designing in this way, similar to language, aims to shape perception, both as a means of communication and as a framework for structuring the world. In that sense, doing philosophy can be designed as well.

Could you elaborate on the concept behind Rapid Autografting? What inspired you to explore biotechnology and human augmentation through footwear design?

The body is an unstable system. We inject it with caffeine, cut it open, and wrap it in materials that partition it from its environment. I wanted to push beyond performance footwear as we know it. Most of today’s footwear innovations are based on the same formula—lighter, stronger, mand ore cushioned.

But what if the next frontier is not external in that sense at all? What if the shoe is not a thing but a phase—something that grows, adapts, and dissolves when it has served its purpose? The idea behind Rapid Autografting is to redefine footwear not as an object but as something entangled with our ever-changing physiology.

Can you walk us through the materials and technologies used in Rapid Autografting?

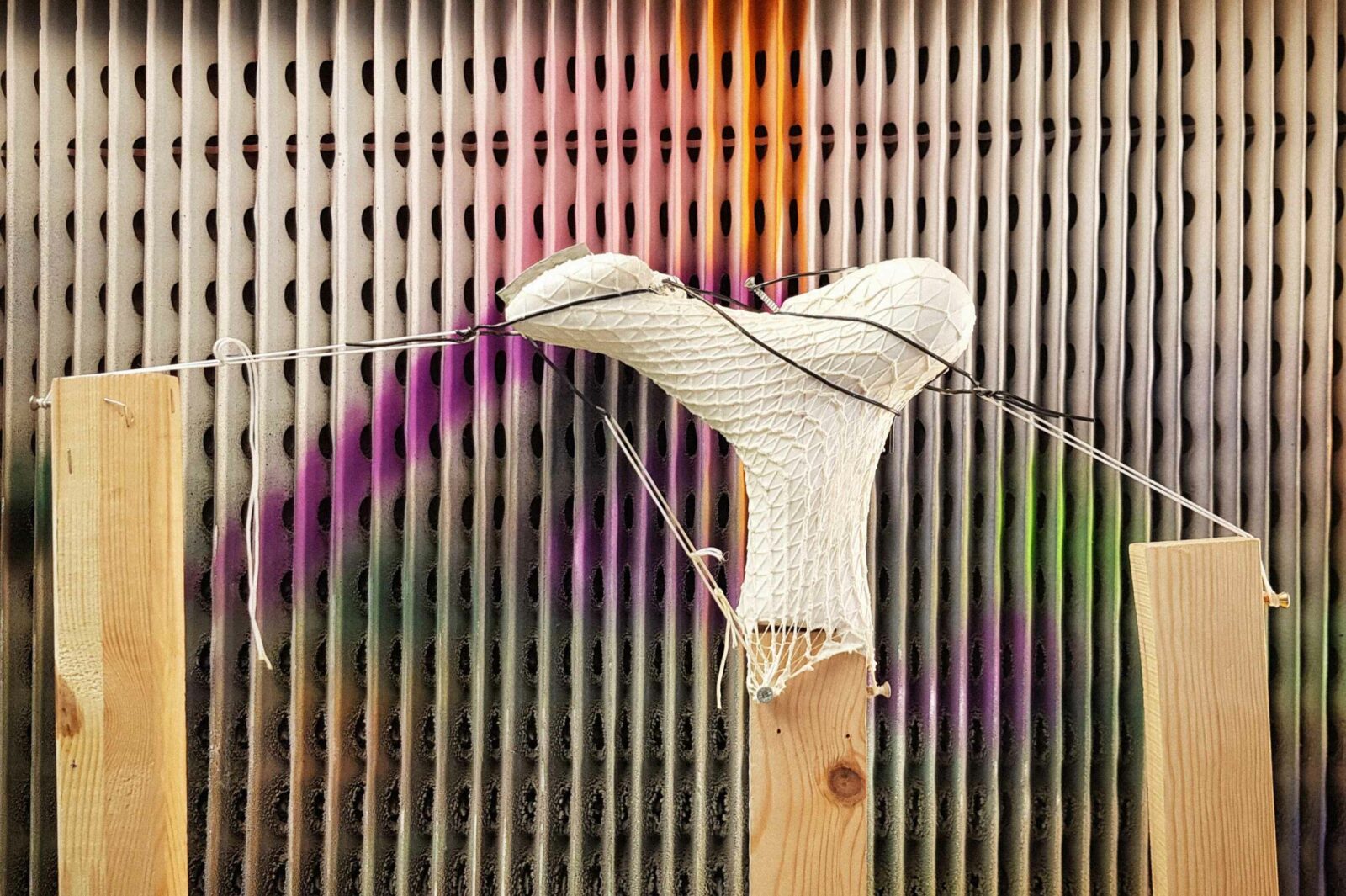

I worked with biofabricated materials like collagen, keratin, and gelatin. The key technology is 4D bioprinting, which is used in biomedical engineering. The idea is that you temporarily transform your foot for a race, a marathon, or a ritual—and after that, your body reabsorbs it. No waste, nothing to discard. It is never thrown away—it ceases to be a shoe.

To approximate this vision, I combined material exploration, 3D scanning, digital modeling, iterative prototyping through 3D printing, and many hands-on experiments. I used stretchable meshes, collagen, latex layers, and a gelatin-based cushioning system.

What considerations did you prioritize when deciding the visual and aesthetic aspects of the design?

The aesthetics emerged from biological logic—soft tissue, connective structures, and the way skin heals. It should make you feel like it evolved naturally rather than deliberately designed. There is also an unsettling quality because it does not look like regular shoes. The ambiguity in the visuals is intentional. It is messy. It does not ask to be liked but to be questioned.

What was the design process of Rapid Autografting, from the initial concept to the final product? What research methods or design techniques were most critical in shaping the outcome?

The design process was an exploration in multiple directions rather than a rigid step-by-step progression. I started by analyzing the foot’s physiological responses during running— perspiration and heat regulation. I spent a lot of time researching and understanding.

My focus shifted to callus. Often dismissed as unsightly, it is a remarkable biological adaptation that strengthens resilience. From there, material testing took over. More biology lab than design studio. If something collapsed, I did not “fix” it. Failure was key.

As a student, how did your academic environment influence the project? Do you think being a student presents unique challenges or opportunities?

As a student, being underestimated can be an advantage—it allows for greater creative risk. Konstfack provided an environment where I could explore such ideas without the immediate pressure of commercial viability or brand alignment. That freedom allowed this project to evolve in a way that might not have been possible within conventional constraints.

The ability to step outside the structured frameworks of industry, even temporarily, can generate insights that become valuable later on. In this sense, students have a unique opportunity to design for possible worlds beyond here and now.

What were the biggest challenges you faced during the development of Rapid Autografting? How did you solve these, and what did you learn from the process?

The biggest challenge was designing for an undefined future. It is like designing a spaceship without knowing the physics of the universe it would fly in. One solution for me was learning to embrace uncertainty. This sounds simple in retrospect, but it was not. I have learned that control can sometimes be limiting and is not always beneficial.

Congratulations on your win at the Global Footwear Awards! What does this recognition mean for you and your future in the sustainable design industry?

Thank you! I am honored to receive this recognition from the GFA, especially in the sustainability category. It is a sign that my ideas resonate beyond the academic context. Design should perhaps not only sustain but also challenge the notion of products as static things. This award indicates that the industry is listening and is open to new ways of designing and innovating responsibly. Now, we can start the real work.

Looking ahead, what areas of design or research are you most interested in exploring? Are there any upcoming projects or concepts that you can tell us about?

I am fascinated by the relationship between humans and technology. One focus will continue to be exploring how movement, materials, and human capabilities can be redesigned, particularly in sports. Emerging technologies are increasingly dissolving the boundaries between product and body. As this distinction fades, so too does the line between what we are and what we might become. Footwear is a unique interface for designing these shifts, and I will continue pushing forward, again, working between disciplines, methods, and perspectives.