Ruiting Xu is part designer, part environmental strategist, and part storyteller, working on spaces where ecology, culture, and daily life converge. With a Master of Architecture from SCI-Arc and a string of international awards for her work on The Vessel Type and other projects, she has developed a design language that is as rigorous as it is poetic. Her experience spans architectural and interior design, environmental performance analysis, and a deep curiosity for how buildings can feel both grounded in place and generous to the people who inhabit them.

In this conversation, we explore her unique approach, examining how ecological systems and human experience influence her creative process. These tools help her push boundaries and explore what it means to turn sustainability from a checklist into a narrative woven throughout space.

Your work emphasizes ecological integration and user experience. Can you share how these priorities influence your design process from concept to execution?

Ecological integration and user experience are foundational to how I approach design. I begin by analyzing the site’s environmental systems, such as precipitation, water movement, and solar exposure, to identify opportunities where architecture can work with, rather than against, its surroundings. At the same time, I consider how people will engage with the space in everyday life. The goal is to create environments that are both responsive to ecological systems and emotionally resonant for users. These priorities guide the project from initial concept through to material selection and detailing.

How does your background in both architecture and interior architectural design shape the way you approach a space?

Having a background in both architecture and interior architectural design enables me to approach projects with a holistic mindset. When designing, I simultaneously consider the broader architectural context, including the building’s form, structural logic, and environmental response, alongside the intimate experience of inhabiting the space. This dual perspective pushes me to think about how larger-scale design decisions translate into sensory and emotional qualities at the human scale. It informs the way I select materials and define spatial sequences between light, texture, and form. Ultimately, this integrated approach ensures the architectural concept is consistently expressed in every detail, creating spaces that feel cohesive and meaningful.

Sustainability is a core part of your practice. Could you describe a moment when environmental analysis significantly changed the direction of a project?

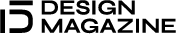

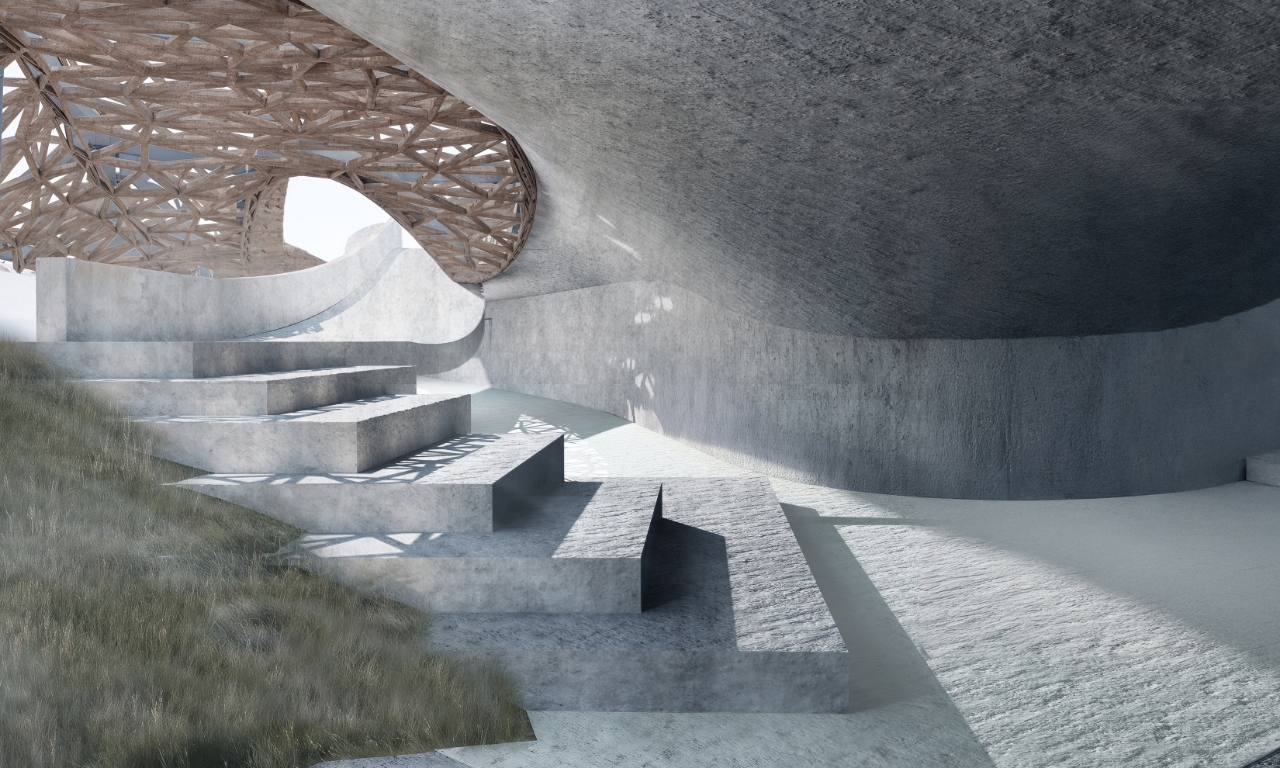

In The Vessel Type, environmental analysis played a critical role in reshaping the design direction. Early studies of seasonal rainfall and local hydrology in Madagascar revealed that water was both abundant and scarce, depending on the time of year. This uneven access made it clear that the project could not rely on a centralized or purely engineered solution. Instead, the design shifted toward a decentralized system of vessels that collect, filter, and store rainwater while also serving as open public spaces. The vessels are partially embedded to protect water from evaporation and contamination, while their surfaces remain accessible and communal. This shift moved the project away from conventional infrastructure and toward a typology that merges utility with cultural and spatial relevance. Environmental analysis was not just a tool for optimization. It reframed the problem and opened up new possibilities for how architecture could serve both ecological function and everyday life.

Can you tell us about a challenge you encountered while balancing aesthetic vision with sustainability goals? How did you resolve it?

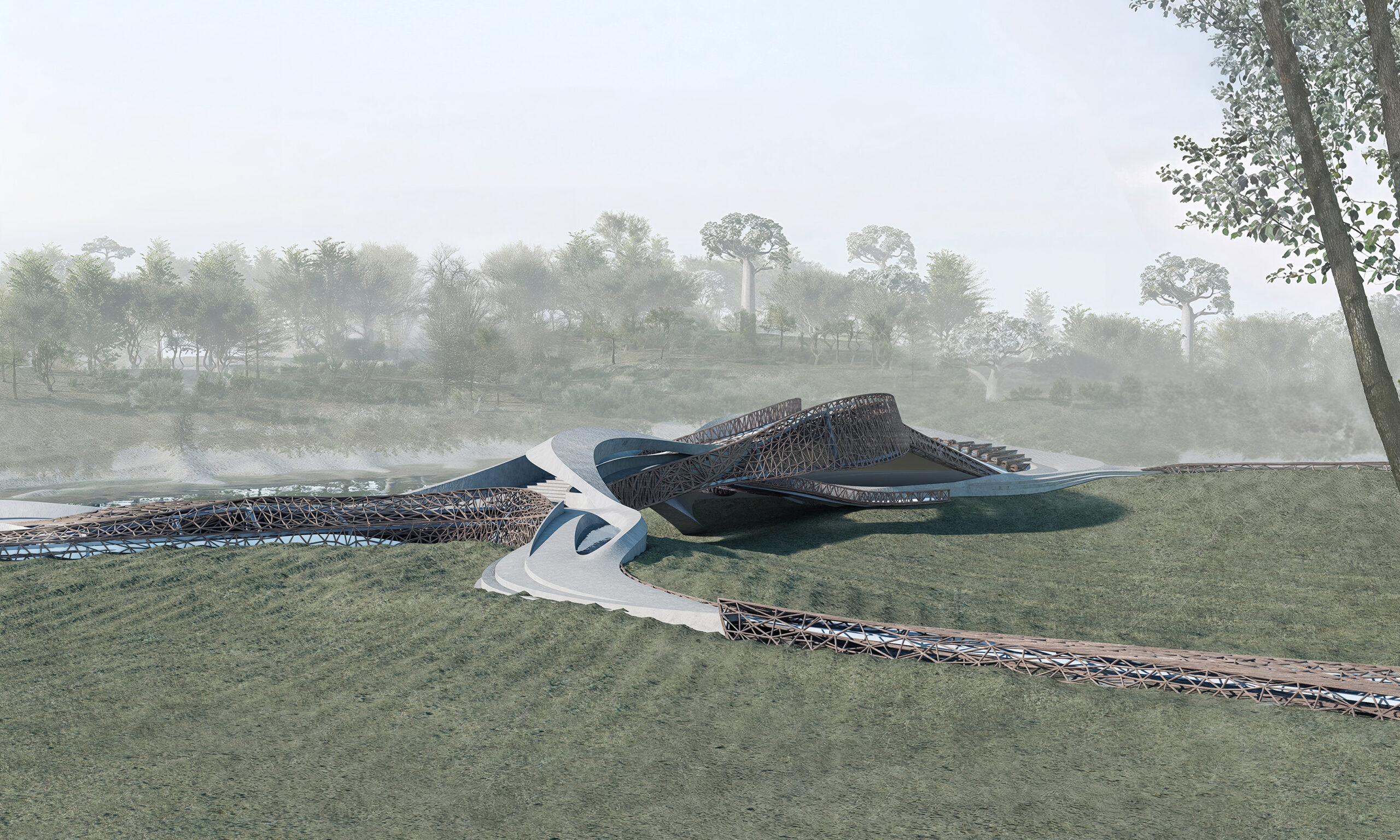

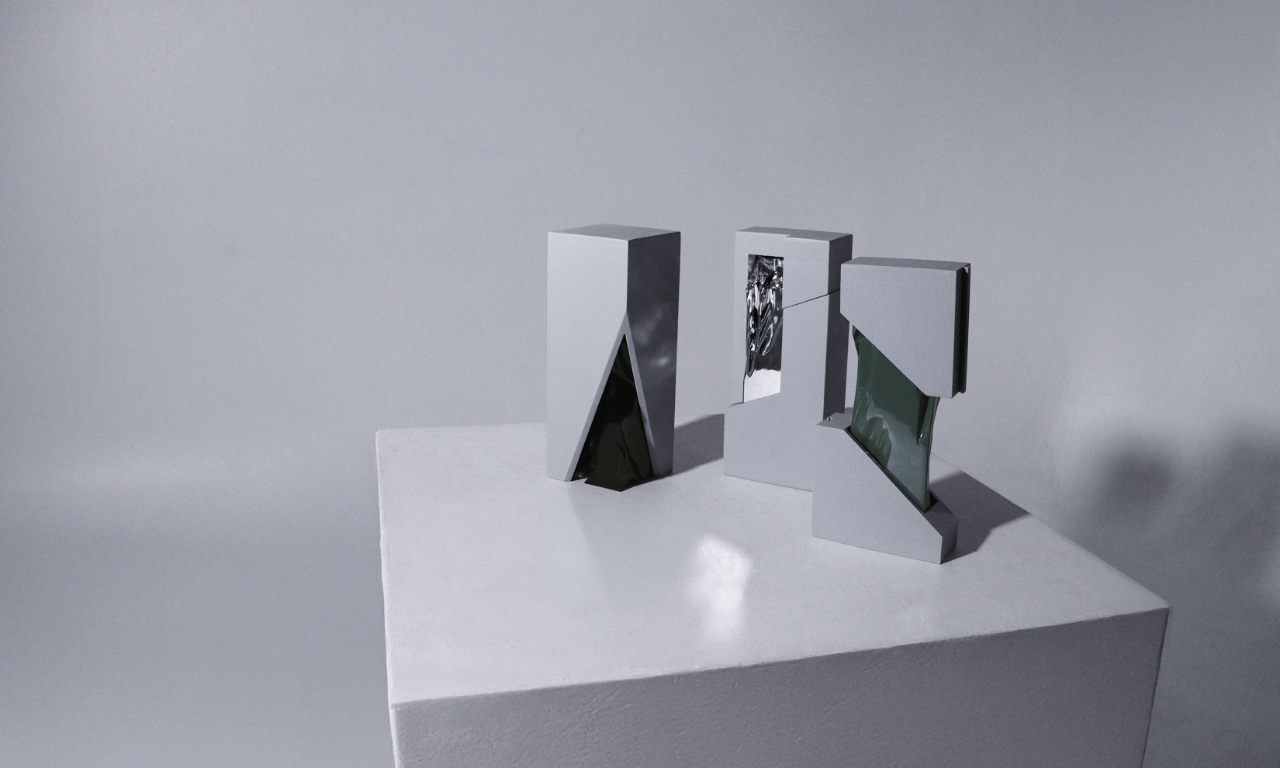

In The Vessel Type, a major challenge was integrating water infrastructure into the built environment in a way that felt spatially generous and culturally grounded, while still meeting environmental performance goals. The project is situated in a climate with intense rainfall followed by prolonged dry periods, so water had to be carefully collected, filtered, and stored for long-term use. From a sustainability perspective, this involved minimizing evaporation, protecting water quality, and ensuring accessibility.

At the same time, I wanted the structure to be more than technical systems. I imagined it as a civic landmark and a communal gathering space that people would inhabit and move through. To reconcile these two priorities, I designed the water system with a layered approach. After surface collection, water passes through a submerged biofiltration process and is stored in partially buried vessels to ensure cleanliness and thermal protection. Above ground, the structures remain open and accessible, offering shaded public space while subtly expressing the presence of the water infrastructure below.

This solution allowed the project to meet performance goals related to water conservation and thermal regulation, while also maintaining a spatial and cultural generosity that was essential to the project’s vision. It became a way of turning sustainability constraints into design opportunities, where performance and presence could coexist.

What tools or technologies have been most transformative in your recent work, and how do you see digital tools shaping the future of architecture?

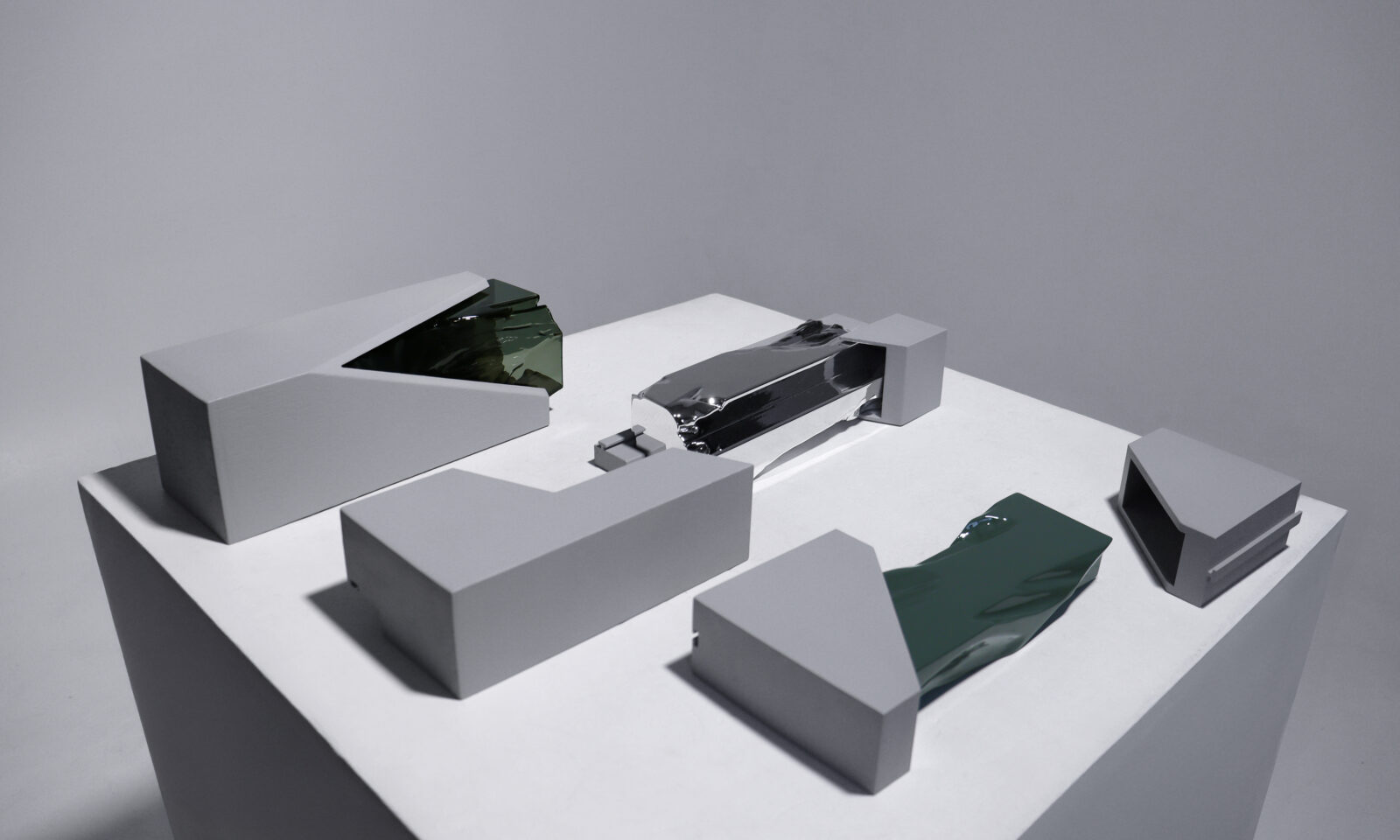

Simulation and physical modeling tools have both played a key role in my recent work. For The Vessel Type, I used climate and water flow analysis to guide early design strategies, and 3D printed topographic models to physically test how rainwater would move across the site and into the vessels. This helped me refine the relationship between landscape, structure, and collection points. I also work with tools like Rhino, Grasshopper, and GIS to explore spatial and environmental systems. I believe digital tools will continue to evolve beyond representation, becoming essential for designing architecture that is performative, adaptive, and grounded in real-world conditions.

If you could design a project anywhere in the world with no constraints, what would it be, and what story would you want it to tell?

I would design a climate-resilient school and community hub in a rural area where infrastructure is limited and environmental pressures are increasing. The project would collect and store rainwater, provide naturally ventilated classrooms, and create flexible spaces for gathering, learning, and local food production. It would be built with local materials and techniques to reduce environmental impact and strengthen community participation. Through its presence and use, it would speak to the possibility of how architecture can respond to both environmental and social conditions without relying on complex systems or imported solutions. It would show that resilience can grow from local knowledge, shared responsibility, and thoughtful design that supports everyday life.