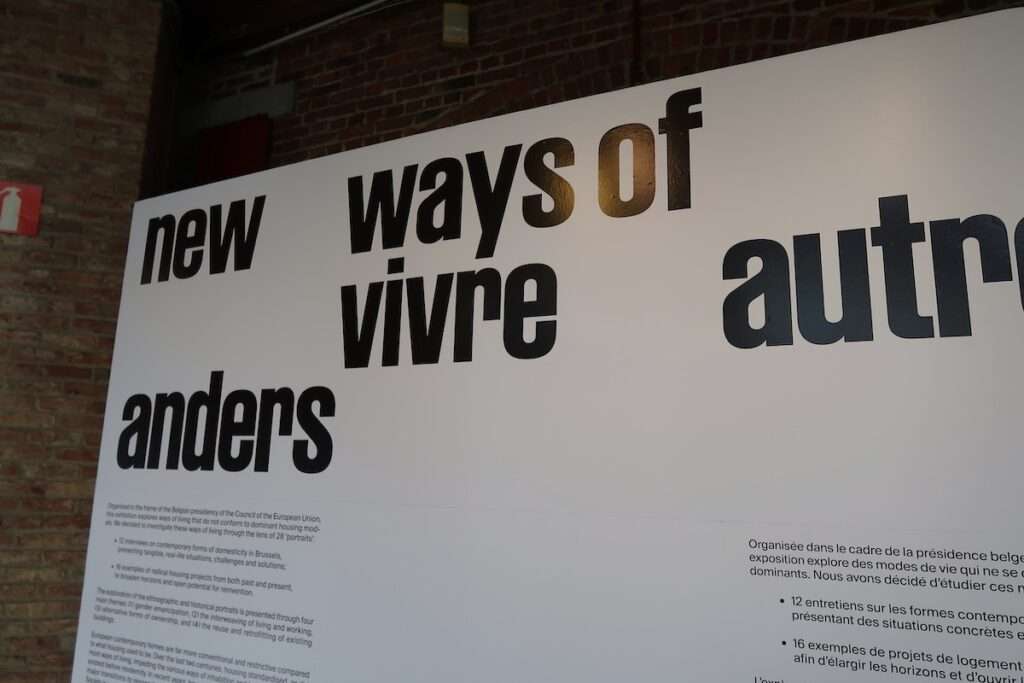

With Brussels Design September in full swing, D5 has attended one of the exhibitions the festival has to offer. Although part of the festival, the New Ways of Living exhibition has been open since May and is coming to an end on September 29. Nonetheless, its topic, focusing on diversifying and changing the traditional housing configuration, is close to the festival’s aim of introducing multifaceted design to the public.

New Ways of Living exhibition consists of four sections— Gender Emancipation, Living and Working, Forms of Ownership, and Reuse and Retrofitting. Each section presents four case studies showcasing different housing arrangements.

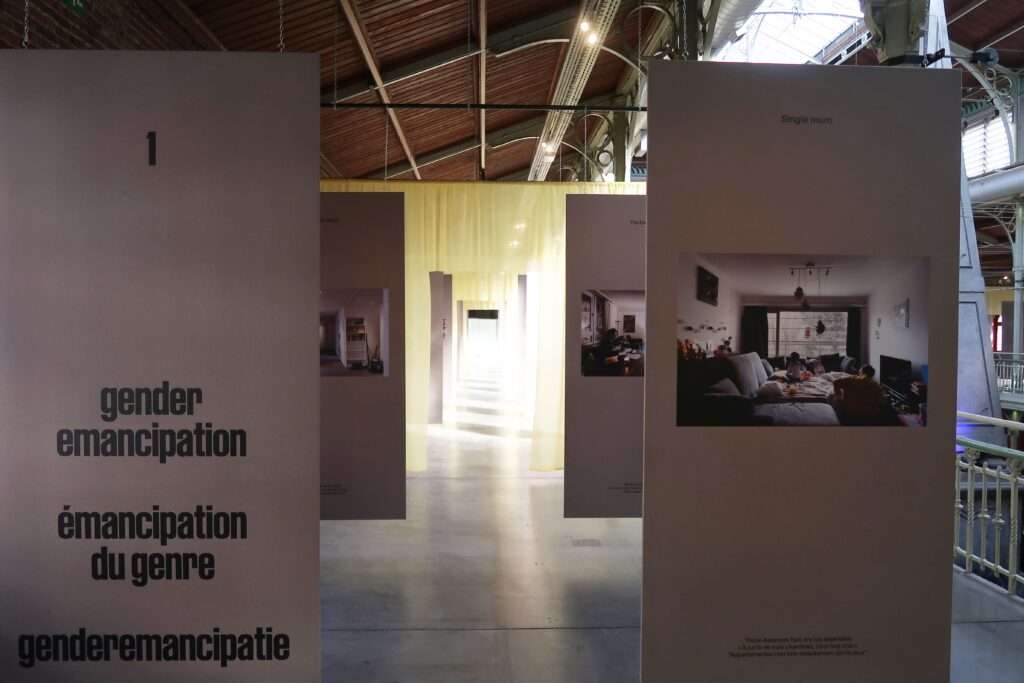

Gender Emancipation

The first one, Gender Emancipation, focuses on case studies of households that challenge the conventional housing norms. “The most common and standardized living arrangements are based on outdated and rigid concepts, namely the classic mum, dad and kids’ family as the normative model. These conventional paradigms no longer adequately reflect the complexities of contemporary urban life.”

Case studies presented in this part of the exhibition challenge gender roles to fit intersectional and queer perspectives. Choosing to live in alternative housing can be a deliberate decision. However, for FLINTA individuals (Female, Lesbian, Intersex, Trans, and Agender), this choice is frequently driven by necessity, as they often face unstable or challenging conditions.

One of the case studies The Doll House focuses on Morphae, Vera, and Alexia who live in a shared apartment and have developed a sense of family. They conveyed that as queer individuals they had “different housing experiences, some pleasant, some ‘terrifying'”, so having people who understand each other and “speak the same language” is liberating.

Living and Working

The second section explores the intersection of living and working. As with COVID-19, many people were introduced to the comfort of living from home, it is however not the first time in history that boundaries between our working and living spaces were non-existent. Examples presented in this section showcase how many households combined the two up until the nineteenth century. Examples include medieval European townhouses, Ledoux’s 1770 ideal city project, early 20th-century weaving workshops in English attics, and New York lofts, repurposed by artists in the 1960s. More recent examples are an artist house in London and a cité d’artistes in Brussels.

As more and more individuals started working from home, today’s households were not developed to accommodate living and working in the same space. Therefore, projects like the House for Artists developed in East London by the Borough of Barking and Dagenham in 2021 are trailblazers in what our future households might look like. Apparata Architects designed the House for Artists consisting of twelve living and working units with rents set at 65 percent of the market value. Residents are chosen by Create London based on artists’ income. Currently, it’s home to twelve artists and their families.

Forms of Ownership

In this section, we get to further delve into the topic of challenging traditional housing with projects that facilitate “alternative forms of housing ownership.” Throughout history and across the world, various alternative ownership models and housing tenures have existed alongside private property. Before private homes and spaces became exclusive and commodified, ownership often relied on reciprocity—mutual exchange for shared benefit. Today, housing is mainly seen as a private commodity and financial asset, leaving those without private homes in precarious situations. However, this dominance also opens the door to creative alternative solutions.

Reuse and Retrofitting

The last section of New Ways of Living shows how renovation, transformation, and repurposing of buildings is the antithesis of demolition in the age of climate crisis and the ongoing housing crises around the globe. The need to protect biodiversity and manage land use pushes cities to increase density and make smarter use of existing infrastructure. The question of heritage preservation also shifts the focus to view the built environment as both a cultural artefact and a response to climate change.

Examples presented at the exhibition focus on reusing spaces, such as a metalworking factory and a car garage turned into innovative housings. Project Artaud in San Francisco, an early example of industrial heritage converted into communal housing, can be compared to more recent efforts like Emil in Anderlecht, Brussels a retrofitted office building for refugee housing.

Projects like the renovation of Tour Goujons, which restored a social housing block and its residents’ dignity, demonstrate the potential of adaptive reuse. Avi Friedman’s Adaptable House model, which evolves with the changing needs of its residents, further showcases diverse housing approaches. These projects illustrate a broad range of solutions and ideas for housing.