Today we’re speaking with Raphaël Ascoli, the founder of Blue Temple. By fusing traditional materials with modern techniques and a keen sense of social justice, Blue Temple is transforming the landscape of affordable housing in Myanmar with the Housing NOW project. In this exclusive interview, we delve into the inspiration behind this unique architectural endeavour, the challenges faced, and the transformative impact of their work.

Photo credit: Alex Dyl

Your journey into architecture and design seems unique. Could you tell us more about your initial discovery of this field and your eventual move to Myanmar to open Blue Temple?

During high school, I wasn’t sure about what I wanted to pursue, so I applied to a range of departments and universities. But when the acceptance letter from the Department of Architecture arrived, something clicked, and I instantly knew that was my calling. The entire process was quite spontaneous.

As for my journey to Myanmar, it was also unexpected. I was working in a commercial firm in Tokyo, Japan, a role that didn’t quite resonate with me. My desire to work on certain projects didn’t align with the firm’s interests, which led to a period of frustration. Eventually, I decided it was time to break free and explore something different. Hence, my decision to be spontaneous and move to Myanmar.

Could you shed some light on how you formed your team and how Blue Temple came into existence?

António Duarte, a close friend and a fellow creative mind, was instrumental in forming Blue Temple. We met during my second year in Myanmar. He’s an artist with a background in architecture and had come to Yangon to express the city’s energy through his art. We met in a local bar, and, over time, we got the idea of undertaking low-cost housing projects. This common interest resulted in the initiation of the Housing NOW project.

I had been working closely with local associates who were experts in bamboo construction techniques. Together, the three of us launched the Housing NOW project right after the military coup in 2021. Before this, our focus was on conventional public space bamboo construction projects. Our initial interactions were exploratory in nature, a fusion of creative ideas aimed at shaping diverse public spaces.

Blue Temple began as a hub for the free exchange of ideas, and over time it evolved to host more philanthropic projects like Housing NOW. Our work in Myanmar has taken a more radical direction, reflecting my political views and aspirations for change.

Photo credit: Nyan Zay Htet

Your use of bamboo as a construction material for low-cost houses is intriguing, especially considering it’s a common material in Myanmar’s vernacular architecture. Could you explain your thought process and what distinguishes your approach?

Well, I can’t claim to have reinvented the wheel. Bamboo has been a cornerstone of construction in Myanmar for centuries. It’s deeply woven into the fabric of local architecture. When I first arrived here, I was eager to learn about various global construction techniques. When I met my associate, we had multiple conversations about bamboo and that was when I felt inspired.

What I’m trying to do is modernize the community and the perception the people have about this traditional art form and craftsmanship, while introducing modern techniques and treatments to prolong the lifespan of the bamboo structure. By adjusting the design, pigments, and employing different chemicals, we can protect bamboo against termites and other diseases for a more extended period compared to traditional methods.

What sets us apart is our exploration of this vernacular vocabulary. We experiment with different design elements, subfloors, and create a unique amalgamation of these elements while still being rooted in traditional architecture.

Myanmar is home to around 320 bamboo species. The variety is astounding, from black bamboo to yellow and green. I believe that there’s no need to stick to just one type; we can explore the potential of the smaller species, which are abundant and very inexpensive. I was fascinated by how the locals used bamboo for everyday necessities, from brooms to fences. I noticed that while people bundled together bamboo to create different structural works, they didn’t exploit it fully, which made me think about the untapped potential. This sub-genre of bamboo architecture seemed to have immense potential.

We didn’t set out by saying that we wanted to build houses using this material, however, it was the end goal. We started small, researching and building tiny prototypes before gradually scaling up their size. This was a step-by-step process that took about three years. After building our seventh prototype, we felt ready to build the real deal. We’ve built 10 houses so far, and although we’re still in the early stages of our development, we’re continuously working to make our mark in this field.

Photo credit: Raphaël Ascoli

Collaboration seems to be a cornerstone of Blue Temple’s work, particularly in involving local communities in project development. How do you handle the construction of houses – do you work with community members or a dedicated group of builders?

Starting from scratch in Myanmar, I had to learn through trial and error, constantly refining the process with each experience. My first big project was a public space with bamboo structures. That’s when I deeply collaborated with the community for the first time. I realized that as much as I could give, the process of engagement and running workshops with the community was not my strong suit. It was a successful project, but the preparation was long, taking 2 years, while the construction was completed in only 3 months.

So, when we began the Housing NOW initiative, we asked ourselves “how can we hijack this entire process and accelerate the whole thing while still being inclusive and engaging the community?” Basically, we needed to identify the right partners – essentially NGOs that had been working closely with these communities for years and understood their needs. They became our implementing partners in these emergency housing projects, facilitating community engagement and identifying their requirements.

For instance, they might specify the need for an 80-square-meter house to accommodate 30 students in a refugee camp. We would then collaborate on deciding the program, the number of units needed, and the affordability. Before construction begins, we have a quick workshop with the community to finalize the layout plan, including partitions, windows, doors, etc. If any issue arises, we call on our NGO partner to facilitate the engagement.

In essence, we act as contractors, enabling us to build quickly and efficiently while being responsive to the community’s needs. About 50% of our workforce is hired directly from the refugee community; the rest are our experienced workers. For a project requiring six workers, we would bring three from our team and hire three from the local community, training them and paying them daily wages. These workers learn the design and can then apply it to their own houses.

While the skills they acquire can’t immediately enable them to build their houses due to lack of funding, it creates potential for long-term collaboration, as they can work on future projects in other camps. However, even with the skills they learn, they can’t build houses by themselves because of a lack of funding. It’s important to remember that these communities are extremely vulnerable. They often depend on donations, especially from NGOs, and may not have the connections or resources to find jobs and become self-sufficient.

Emergency housing projects prioritize immediate shelter and basic needs, pushing sustainability and job prospects to the back seat. The work environment is challenging because, while there’s a clear need for more, immediate survival takes precedence. At the end of the day, the workers do acquire useful skills – most of them have already worked with bamboo, so they’re not starting from scratch. But without funding to source materials and tools, they can’t immediately put these skills to independent use.

Photo credit: Raphaël Ascoli

You’ve been collaborating with a variety of NGOs, some focused-on healthcare, others on education. Could you tell us more about how these collaborations have been formed and how you’re leveraging them to build homes for those in need?

We’ve been focusing on partnering with housing and shelter coordination NGOs, although we’re still very much in the startup phase. One of the prominent organizations we’re looking into is the UNHCR, which has programs for emergency housing in various parts of Myanmar. However, our current partners are smaller NGOs whose primary focus isn’t necessarily housing, but who see the benefit of housing projects for their broader initiatives.

For instance, we’ve worked with Medical Action Myanmar, an NGO engaged in healthcare provision such as distributing malaria medication and other drugs to vulnerable communities, often residing in slums. Working with them has been a rewarding experience; we’ve already built two houses together. While their focus isn’t housing, they understand the significant health benefits of providing stable housing to those who might otherwise be homeless.

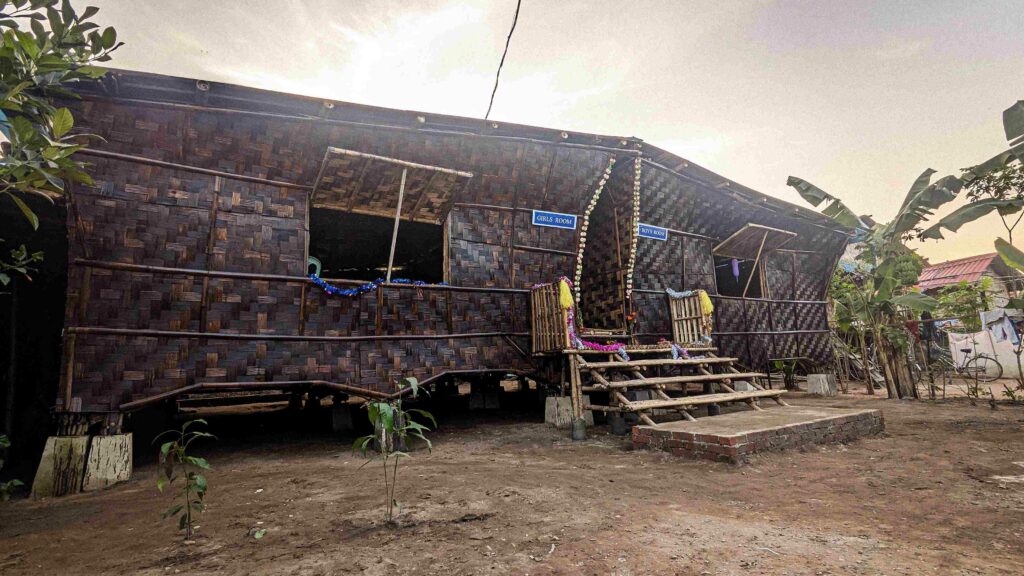

Another organization we’ve collaborated with is SONNE International, an Austrian charity specializing in educating young girls in vulnerable situations. They support schools and educational programs in refugee camps in the northern part of Yangon. Through our partnership, we were able to construct a dormitory/orphanage within a refugee camp to provide shelter for newcomers fleeing other parts of Myanmar. This effort not only offers a secure place to live but also supports their education by providing them with a beneficial living environment.

We recently ran a crowdfunding campaign that raised enough funds for us to donate houses directly. Rather than giving directly to the communities, we thought it more effective to donate the houses to NGOs already engaged with these communities. This enabled us to approach NGOs with the offer of two or three houses, rather than asking if they had a project we could assist with. This approach has helped us quickly establish connections and conversations within networks we weren’t previously connected with, fostering relationships that could lead to more projects in the future.

Photo credit: Nyan Zay Htet

Could you provide more details on this fundraising initiative? How can interested parties contribute to these efforts, and where should they reach out if they want to get involved?

This isn’t a traditional crowdfunding effort where donations can be made through a dedicated website. We do have a lot of potential projects where communities ask for houses, so there is indeed a big need. We have already contacted the right people to implement these projects, so if there are people that would like to contribute, they could either reach out to me or to one of the NGOs that I’ve mentioned before, like Medical Action Myanmar or SONE International.

For example, if donors would like to focus on medical aid, we are developing a hospital inside a slum, in the northern part of Yangon, where a big need for healthcare resides. Slums are completely left alone, and the communities are marginalized, it’s atrocious to see the living conditions these communities are in. If some of the donors want to focus on clinics and health care, I could get them in touch with the NGOs that focus on this topic, or any other, like education.

The cost of building a housing unit is approximately $1,000 and takes about a week to complete. Any contribution, therefore, can significantly impact these communities. Additionally, donors, especially organizations seeking to highlight their philanthropic activities, can benefit from showcasing the tangible results of their contributions by sharing photos on their websites.

It’s worth noting that we commence building only when we’ve raised at least $4,000. This is due to the considerable logistical effort involved in transporting materials, tools, and organizing the workforce. Our aim isn’t to construct individual houses, but rather to address the broader infrastructure challenges in Myanmar with larger projects. Once we have the funds for at least four houses ($4,000), we start building.

Photo credit: Raphaël Ascoli

As we move towards the future, what are Blue Temple’s plans and aspirations for its projects and initiatives? Are there any innovative approaches or new areas that you’re currently exploring?

At Blue Temple, we are open to a diverse range of projects. Currently, we are concluding an archaeology project in Malaysia, where we’re investigating 2000-year-old Hindo-Buddhist ruins on the border between Malaysia and Thailand. Our work involves digitally reconstructing these ruins to reimagine their past state. We’ve also innovated an interactive element for tourists: windows with stickers of the reconstructed buildings that overlay the ruins on the current site. This project sees us collaborating with archaeologists and architecture professors, and, while I never imagined venturing into archaeology, it’s become clear how transferable architectural skills are across different fields, including design thinking, computational design, and 3D modelling.

We recently embarked on our first project in Africa. We’re constructing a 300-square-meter warehouse in Madagascar for a company focused on reforestation. They aim to plant a million trees a year, turning the “Red Island” green again. This project will allow us to continue exploring the potential of small bamboo bundle structures. The client’s vision aligns with ours—they want the entire building to be made of bamboo, symbolizing their mission of reforesting the region.

Despite being a young design studio, we’ve started to gain momentum after seven years of hard work. However, we’re facing a challenge: as our projects grow in size and number, our team is shrinking. We’re not aiming to become a large company but are focused on finding the right people. Currently, I’m training young Burmese architects, who, as they grow, often dream about seeking higher education or opportunities abroad. While I’m happy for them, we’re in desperate need of like-minded architects. While my commitment to teaching and hiring from Myanmar remains strong, we’re also considering expanding our team internationally.

Photo credit: Matias Bercovich

Blue Temple’s work in Myanmar is a distinct example of how architectural practices can address complex social challenges. By collaborating with local communities and NGOs, the venture is contributing to the provision of affordable housing and giving people the chance to be directly involved in the process. Raphaël Ascoli‘s emphasis on vernacular architecture underscores the potential of local resources in the development of sustainable housing solutions. As they expand their reach beyond Myanmar, it will be interesting to see how Blue Temple adapts its approach to new contexts and continues to evolve in the architectural landscape.

If you’re an architect with a passion for creating meaningful change or someone interested in contributing to their mission, Blue Temple invites you to join them. To explore potential job opportunities or to contribute to their fundraising efforts, you can reach out to them directly via their website. By joining hands with Blue Temple, not only can you partake in their vision of transforming communities, but also in building a sustainable and inclusive future.