What if the secret to a breathtaking space lies in the light? At Maura Clark Studio, that’s precisely the belief guiding Maura’s innovative designs. With a focus on creating a unique language through light, she enhances our perception of interiors, turning everyday spaces into captivating experiences. Her fixtures illuminate and elevate, infusing warmth and character while transforming the ordinary into something truly special.

Maura’s journey began at Penn State University, where she earned both a BFA and BA in painting and history. After graduation, she immersed herself in the vibrant art scene of New York, working in galleries and as a curatorial fellow at the New Museum. It was at The Rhode Island School of Design that she discovered her true passion for interior architecture and design. Her experience at several lighting design firms ignited her creativity, allowing her to create custom fixtures that breathe life into spaces.

Now, as a senior lecturer at Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), Maura shares her knowledge and passion for lighting design with students, teaching them about the delicate relationship between light and space in their interior architecture graduate program. Each fixture produced at Maura Clark Studio is crafted with care, made in-house and custom to order. She has worked with various high-profile clients from LA to NYC, including a Michelin Star restaurant and private celebrity homes.

Let’s explore Maura’s luminous world and discover how her designs bring spaces to life.

Maura, your journey from studying painting and history to lighting design is intriguing. How did your artistic background influence your decision to focus on lighting?

Light was always a part of my practice. Early on, during my BFA in painting, I began to focus on the idiosyncratic differences between color and finish. Almost all of my work focused on a slight deviation in hue, saturation, or gloss across a canvas surface. I worked on these paintings entirely in the northern morning light of my undergraduate studio. I began to note how these paintings only felt right in the certain light that I had painted them in. Deeming them my ‘morning paintings,’ I became obsessed with how to light them to show off the subtle details I was set on.

After moving to New York, I worked at the New Museum in a fellowship that afforded me the opportunity to be a part of exhibition installations. Working in this environment was when I realized that I could just do lighting. Coming from a small town, I hadn’t thought about ‘light’ as a field. All of a sudden, things opened up to me.

I started to look into architectural schools that would allow me to focus on lighting and really play with emotion and the ephemeral nature of architecture and design. Once I saw how light affects my environment, I never stopped thinking about it.

How do you balance running your design studio with teaching at RISD? Do the two ever influence each other?

It’s definitely a balancing act. I often travel for work as I have projects on both coasts, but in the spring, I head east to teach and stay put for the semester. I find that the months when I’m teaching feel contemplative, often engaging in more research and reading marked by longer quiet stretches of driving around the coast to visit family and friends. Between working with students, going to lectures, and reflecting on readings, these months feel like the impetus for the rest of the year’s work.

You’ve designed some incredible custom fixtures. Can you share the story of one that holds a special place in your heart?

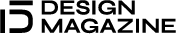

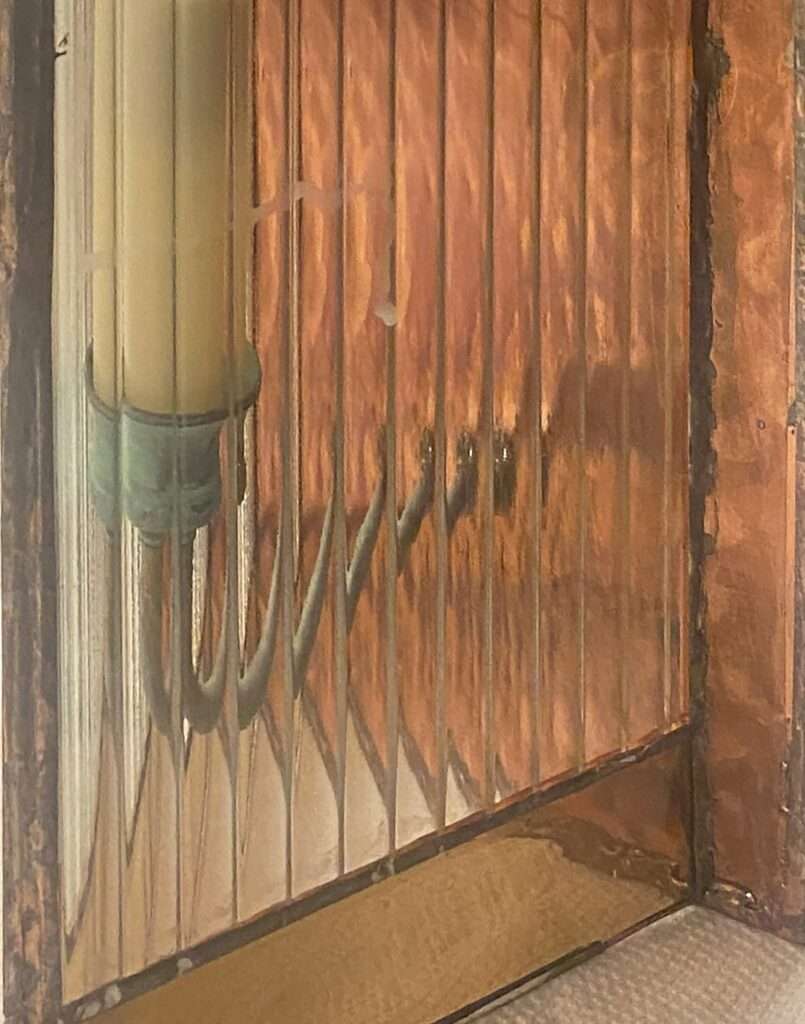

Right now, I’m working to launch my own line of fixtures. This has been several years in the making and has been both challenging and rewarding for me. I started to feel a pullback to referencing artists and ideas that I was influenced by as an undergraduate, and there’s a soft voice that’s been coming through in the process of making. Overall, it’s been a wonderful way to step back into physical practice as I’ve been working on making the pieces in my own studio by hand.

Your work has such a soft, tactile presence. How do you approach blending the technical and the artistic in your designs?

I try to start with the artistic idea of a space. Thinking more about how the light should feel, or what should sparkle, or what should be in shadow. It’s all about perception. Approaching a project this way allows me to hold an image of it in my mind as I try to navigate the more technical aspects of architectural lighting. After that, I start to worry about code and footcandles and controls. The technical parts of lighting design are mostly just problem solving–finding a solution to the artistic idea that I’ve already imagined.

Lighting is such a powerful tool in interior architecture. How do you think it influences the perception of space in a room?

I think lighting is the perception of a space. The process of perception (usually) begins visually; we read a space through light and form. A pattern enters our eyes and has no meaning other than lightness and darkness; we understand that pattern (image) through the attributive process where we assign meaning to what we’re seeing; the information we just gathered is what forces us to understand expectations of our environment; and then we form a feeling. Even though that last step of visual perception is emotional and will have the influence of sound, smell, and temperature entwined in it, it is the initial signal of shadow and light that moves our visual experience. Le Corbusier has an incredibly famous quote about form and light: “Architecture is the masterful, correct, and magnificent play of volumes brought together in light.”

Lately, we’ve seen a trend where people, especially online, seem to “hate the big light.” Why do you think people have such strong reactions to different types of lighting?

Lighting is personal. There’s a strong relationship between light and comfort and it varies among individuals and cultures. I think that the ‘big light’ topic is a great example of comfort and culture. The ‘big light’ – which usually refers to a residential setting with a semi-flush mounted or surface mounted, centrally located ceiling light with 1-3 lamps (read: light bulbs) – is a strong, one-dimensional light. That means the light it gives off may feel harsh and is most likely misplaced for the purpose of the room.

Culturally, in the States, we view overhead lighting or overlit spaces in general to be reflective of more corporate, educational (K-12), medical or commercial environments. Our homes are usually marked by more local lighting, softer approaches, and scattered lighting that ties us to tasks or highlights architecture. Many individuals aren’t aware of the differences between how we use lighting to signal typologies in architecture, but even those who aren’t aware may still have opinions on how different lighting strategies make them feel.

The ‘big light’ has a history, or maybe a tradition, of being either too bright, or too dim, or too green or too blue. However, to those who dislike it, it just never feels right. In terms of comfort, this light isn’t just reminiscent of places, aesthetics, and activities that we want to keep out of our houses – it’s often not functional for the tasks of the room. The big light feels like a big brother, and in our bedrooms, when the sun goes down, we want to turn on a small table lamp and feel cozy, not watched.

Do you think the rise of smart lighting and automation is changing the way we think about interior design?

Absolutely. Automation and smart lighting has changed a lot of the technical aspects of lighting design, but in terms of interiors, I think the future of lighting allows more flexibility in a space. We know that mood is created through lighting, so with these advancements, we are able to shift color temperature or brightness, and adjust scenes effortlessly.

I feel like this impacts smaller spaces or spaces that want to function in multiple ways. A local coffee house may have a set scheme of lighting for the daytime and, at sunset, begin to shift into a different scene for the evening. This small change will affect mood and perception of the space – pivoting from one focal point to another. But it could also signal a change in the use of space – maybe transforming into a bar. Automation really opens up the ability to change a space seamlessly according to available sunlight, time of day, use of space, or personal preference.

With these advancements, however, I think it’s important to note that the downfall of change is rapid turnover. Because engineers are developing new adaptations so quickly, we don’t get as much time with each new technology before there’s an update, and honestly, that is the frustrating part of being in a field that is deemed both tech and art. Especially when the art is large-scale buildings and projects over the course of several years. I have to be aware of that turnover or understand which system will catch on because I want to be implementing technologies and devices that will last.

Finally, what’s the most rewarding part of your work—whether in the studio or the classroom—that keeps you passionate about lighting design?

The mood. I just love the way that good lighting affects architecture. There are so many different approaches to one single space and I absolutely love running through the different ways in which I can help an interior designer or architect create a vibe, a thought, an emotion, a story in their space.