In this Q&A, we speak with Lotte Scheder-Bieschin, recipient of the Emerging Architect of the Year award at the BLT Built Design Awards, about Unfold Form, a construction system that challenges some of the most taken-for-granted assumptions in contemporary building. Developed within the ETH Zurich Block Research Group, the project rethinks how concrete floors are formed, proposing a lightweight, reusable formwork that replaces material excess with structural intelligence.

Unfold Form draws on principles of curved-crease unfolding and bending-active geometry to transform flat-packed plywood components into a self-supporting, corrugated formwork assembled on site in just 30 minutes. The system enables the construction of vaulted concrete floors that rely on geometry rather than reinforcement, significantly reducing both concrete and steel while producing an expressive architectural result that is inseparable from its structural and fabrication logic. Tested through full-scale demonstrations in Zurich and Cape Town, the project positions research, experimentation, and construction as a continuous design process rather than separate stages.

In the following questions and answers, Lotte Scheder-Bieschin reflects on her path from structural engineering to architectural research, the hands-on development of Unfold Form, and what it means to receive BLT recognition while still actively shaping the project toward real-world application.

Can you tell us a bit about your background? What first drew you to architectural design?

I have long been fascinated by how complex geometry and simple physical principles can lead to both expressive spatial qualities and structurally efficient solutions. I initially trained as a structural engineer and became increasingly frustrated by the strong separation between disciplines, which often results in fragmented outcomes. This led me to pursue an architectural master’s programme focused on integrative design, combining computational design, digital fabrication, material behaviour, and structural geometry.

I later continued with a PhD under Professor Philippe Block, whose work on reinterpreting historic structural principles strongly shaped my thinking. I am very grateful to have had the opportunity to pursue this research at ETH Zurich, where the academic environment made it possible to develop the work with both intellectual freedom and strong technical support. Through this path, I found a way to pursue my passion for architectural design while connecting it with real-world constraints such as sustainability, fabrication, and construction.

How would you describe your personal design philosophy and how did it influence your approach to Unfold Form?

I believe that architectural expression can emerge naturally from informed structural and fabrication logic, rather than being applied afterwards. Design is most convincing to me when geometry, structure, and fabrication are developed together. Unfold Form reflects this integrative approach and is conceived as a construction system rather than a fixed form.

Another key aspect of my philosophy is accessibility. Instead of relying on highly specialised fabrication technologies, I am interested in systems that are simple, robust, and broadly applicable, without sacrificing performance.

How did you come up with the vision for Unfold Form? Was there a specific moment, model or problem that made you think “this could really work”?

The underlying motivation of my PhD was the observation that structurally efficient vaulted concrete floors are rarely built today, mainly due to the cost, waste, and complexity of state-of-practice formwork systems. I therefore set out to explore an alternative formwork approach based on simple geometric principles, in particular curved-crease folding.

The decisive moment came through hands-on experimentation with simple paper models. When I reversed the principle from folding to unfolding, I realised that a flat-folded component could unfold into a structurally effective three-dimensional form with strong potential for rapid on-site deployment.

How would you describe Unfold Form to someone with no background in architecture or engineering, and why does this lightweight, reusable formwork for vaulted floors allow for significant reductions in concrete and reinforcement compared to conventional slabs?

Concrete needs a mould to give it shape while it hardens. In most buildings, this mould is flat, resulting in flat slabs that require large amounts of concrete and steel reinforcement. Corrugated vaulted floors, by contrast, use geometry to carry loads more efficiently, mainly through compression, allowing a significant reduction in concrete and eliminating the need for reinforcement. However, formwork for such geometries is far more complex than flat panels and is often produced as one-off, waste-intensive moulds using digital fabrication. This added complexity and waste can limit applicability and undermine the sustainability benefits of vaulted floors.

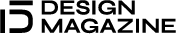

Unfold Form addresses this challenge by using a lightweight kit of components made from simple plywood plates that unfold on site into a corrugated vaulted formwork. The result is a more sustainable construction system that reduces material use and waste, while also introducing a distinct architectural character expressed through the ribbed vault visible from below.

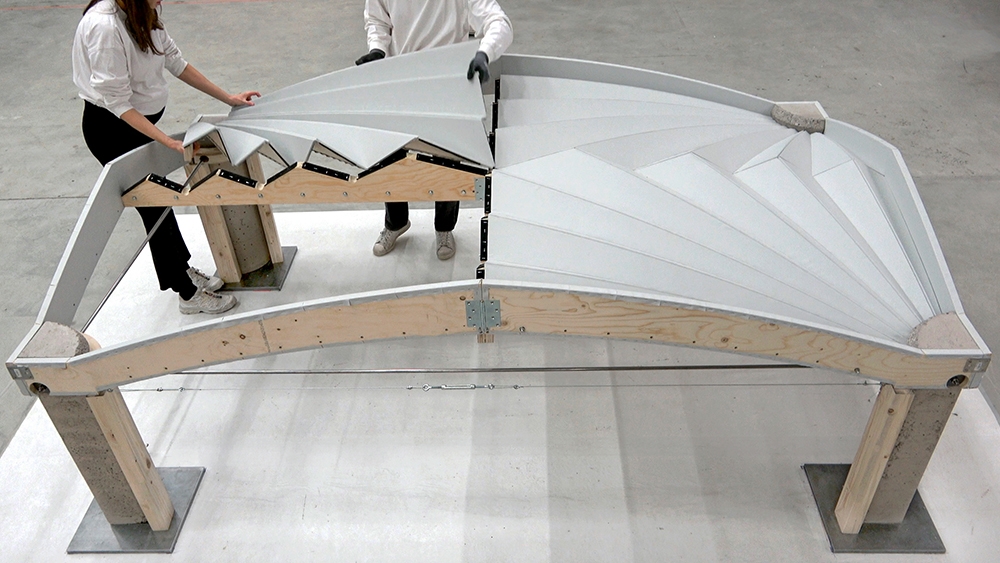

What happens during the 30 minutes of assembly, from the moment the flat-packed, low-cost elements arrive on site to the moment the formwork is ready for casting, and how does this fast setup make the system adaptable to both high-tech and low-tech construction environments?

The formwork components arrive on site flat-packed, which makes transport and handling efficient. A small team can unfold and connect the elements into a stable frame without heavy machinery or specialised labour. This speed and simplicity significantly reduce on-site effort and coordination, making the assembly process robust and reliable for construction practice.

Equally important is how the components are made. They are fabricated using simple two-dimensional cutting processes and basic assembly tools, rather than advanced multi-axis machines typically used for complex formwork. This makes the system adaptable to both industrialised and resource-constrained construction environments.

What were the most difficult moments in the development of Unfold Form and how did you navigate them as a student leading a research-driven project?

One of the main challenges was scaling up from small experimental models to architectural-scale prototypes while ensuring structural reliability and repeatability. This required extensive work on computational modelling, structural design, detailing, and fabrication testing, particularly for the curved hinges, which were resolved using textile connections.

A particularly memorable moment came during the large-scale unfolding, when we saw how precisely the formwork geometry developed and verified that it could safely carry our weight. That was a powerful confirmation that the concept was viable.

What, if anything, would you do differently if you could redesign or re-build Unfold Form now, knowing what you know from the Zurich and Cape Town demonstrations?

The demonstrations confirmed the robustness of the core idea, while also revealing opportunities to further simplify connections and logistics. Future development will focus on improving scalability. At the same time, I am keen to explore additional design possibilities, including aggregated vaulted floors, barrel vaults with parallel corrugations, and funnel-shaped columns, which build on the same underlying principles while expanding the architectural and structural range of the system.

How does it feel to receive an “Emerging Architect of the Year” award while still a student, and how does that recognition affect your confidence, your sense of responsibility, or even the pressure you feel about what comes next?

I am very grateful for the recognition. It is especially important to me to share this moment with my team, including Mark Hellrich, and my advisors, Professor Philippe Block and Dr Tom Van Mele, as well as the many other supporters involved.

It is encouraging to see that research-driven, system-oriented design approaches are recognised beyond academia. The award brings motivation and confidence to continue developing Unfold Form, and it also comes with a sense of responsibility to pursue the project further and work towards making a meaningful contribution.

What are your long-term ambitions for Unfold Form and for your own career? Where would you like this system to be used in the future, and what advice would you give to other students who want to tackle big structural and environmental questions through design?

My next goal is to bring Unfold Form into practice through a spin-off: www.unfold-form.com. I am currently exploring the most suitable strategy while continuing to address the technical challenges required for large-scale application. There has already been interest from different regions, and I would love to see the system realised in built projects, particularly in housing, education, and low-carbon construction. More broadly, I hope the system can contribute both sustainable benefits and architectural quality across a wide range of contexts.

For students, my advice is to focus on a clear underlying system, test ideas physically, and persist. Rigorous design can lead to meaningful change.